Mobile money taxation is, for some, a controversial topic. One the one hand, it is critical for developing countries to increase domestic revenue in order to finance public goods and services and achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. One the other, mobile money is seen as something of a development success story, providing access to financial services to millions of people. With the challenges of raising sufficient tax revenues exacerbated by the pandemic, African governments may be tempted to raise sorely needed tax revenue by taxing low-hanging fruit such as the nascent digital finance and mobile money sectors. But these taxes, and in particular taxes on mobile money transactions, have attracted much criticism from those who fear they will undermine the development gains enabled by mobile money to date.

A recently published GSMA paper aims to engage stakeholders who often speak at cross-purposes on the subject: government policymakers, development practitioners, and industry representatives. The paper explores the motivating forces and unintended consequences of taxing mobile money transactions by examining the cases of four countries where these have been proposed: Uganda, Cote d’Ivoire, Malawi, and Congo-Brazzaville.

Motivating Factors

For the paper, we interviewed stakeholders from the case study countries, including tax policymakers and administrators, to better understand the reasoning for implementing a tax on mobile money transactions. A desire to tax the informal economy was a principal motivating factor. With up to 40% of economic activity and more than 85% of employment in sub-Saharan Africa taking place in the informal sector, there is a perception, fair or otherwise, that this segment of the economy, which uses mobile money extensively, is not contributing its share of tax revenue. This was compounded by a lack of understanding of the nuances of mobile money businesses models at the policy level where the value of payments circulating in the system was seen as a legitimate target for taxation rather than the income generated from it. A lack of capacity to accurately model how the taxes might impact overall tax collection further exacerbated matters.

However, perhaps the most significant factor was that of political economy. Taxation is inherently political, and mobile money taxation is no exception. These policies create winners and losers, and it seems that those in favour – the president, high-ranking public officials, and the banking sector – seemingly had a stronger voice than those who opposed – civil society, development actors, and mobile money businesses. So much so that established policy processes were often by-passed in a rush to implement the taxes.

Unintended Consequences

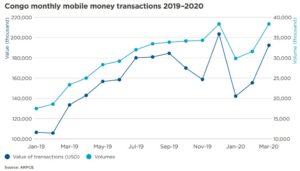

However, the prevalent use of mobile money in the case study countries meant that users had more political leverage than originally perceived. Public outcry about the proposed taxes was such that they were either partially reversed (Uganda, Congo), adapted so they would not fall on consumers (Cote d’Ivoire), or completely abandoned (Malawi). Where mobile money transaction taxes were ultimately implemented, a sharp drop in transaction values was seen in the immediate months following. This was in part due to larger transaction tiers migrating to the banking system where they did not attract similar taxes. With the poor seemingly bearing a disproportionate burden of these taxes, accusations of regressivity abound.

Further, despite initially exceeding the target for the mobile money tax by 37%, the Uganda Revenue Authority reported an overall decline in tax receipts from the telecoms sector, caused in part by the reduction in mobile money activity. In Cote d’Ivoire, where the sector specific tax was borne by the operators, providers reported delaying plans to invest in mobile money network infrastructure, particularly in less profitable rural areas, due to reduced profits. The net result is that instead of being a source of additional revenue to fund government spending, the taxes have served to undermine national development targets, including financial inclusion and plans to digitise economies.

Avenues for future research

The result of secondary research and interviews with 30 key stakeholders, the paper’s aim was to begin exploring the relatively new topic of mobile money taxation and to increase understanding about its causes and consequences. But many questions remain. For example: How regressive are taxes on mobile money? What is the impact of mobile money taxes on its usage, on government revenue, and on the service’s profitability? Can digital financial services be leveraged to facilitate tax payments and increase public revenues? What would good policymaking in this area look like, given the particular contexts and constraints faced in developing countries? It is questions such as these that the wider research community, including the ICTD’s new DIGITAX program, may want to pursue.

Addendum

To learn more about the paper’s findings and hear a more full discussion of the topic, please join us for a webinar on the topic on July 14th featuring Professor Njuguna Ndung’u (Director of the African Economic Research Consortium and former Governor of the Central Bank of Kenya), Professor Mick Moore (Senior Fellow, ICTD), and Dr. Waziona Ligomeka (Director of Policy, Planning, and Research at the Malawi Revenue Authority). Register here to attend and participate in the discussion.

This piece was edited by Rhiannon McCluskey.