Last week, the Institute of Development Studies hosted its 50th anniversary conference titled “States, Markets and Society“. As part of the conference, the ICTD hosted a panel on the theme of taxation and fiscal contracts in Africa. The panellists were ICTD’s research directors Wilson Prichard and Giulia Mascagni, our Capacity Building Manager Jalia Kangave, and the CEO Mick Moore chaired the discussion.

Who pays domestic tax in Africa?

In order to talk about fiscal contracts between the state and citizens, it is important to understand who pays domestic tax in Africa. The presentation began by answering this question, debunking some widely held views.

The poor pay more tax than you think

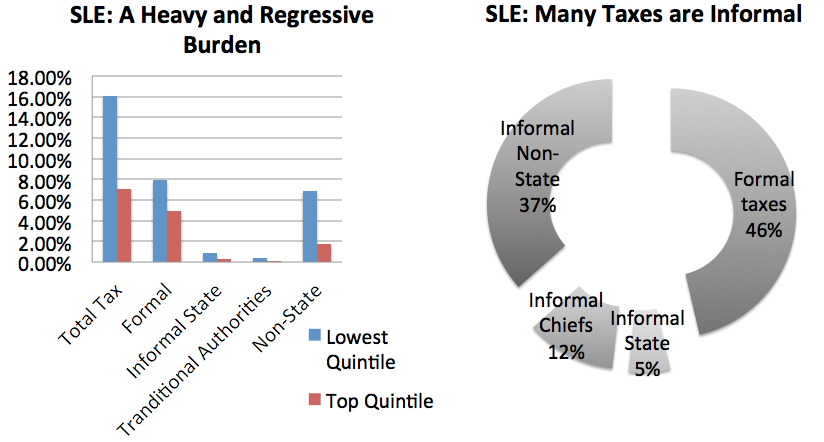

First off, the poor pay more tax than you might think. ICTD research in Sierra Leone and the Democratic Republic of the Congo has revealed that the poor bear a heavy tax burden. In the DRC, the burden is between 20 – 40% of people’s income. The tax burden is also regressive; in Sierra Leone the poorest quintile pay taxes equivalent to 16% of their income, while the top quintile only pays about 7%. Many taxes the poor pay are informal, as can be seen in the diagram below. More than half the taxes in Sierra Leone are paid informally to state agents (bribes) or chiefs and other non-state actors. As these payments do not end up in government coffers, this has important (negative) implications for strengthening the social contract.

The rich pay less tax than they should

How about the rich? Research conducted by the ICTD and the Uganda Revenue Authority revealed that the rich pay much less tax than they should. Out of a group of 60 lawyers from top commercial firms, only 12 paid personal income tax in 2012. Although 12 Ugandans paid more than $180,000 in customs duties in 2014, none of them paid personal income tax. In the same year, only 5% of directors of top taxpaying companies filed tax returns.

Across Africa, there is significant overlap between economic and political elites, and so the same people who pass laws and run the government are the ones who benefit from a regressive system of tax enforcement. In Uganda, the researchers found that out of 71 government officials, most of whom own businesses such as hotels, schools and media houses, only one paid personal income tax between 2011 and 2014. This presents another serious challenge for strengthening the social contract, as when those who have the most money don’t contribute, those with less see the system as unfair and illegitimate, and are less willing to comply.

Business taxation is more taxing on small firms than you would imagine

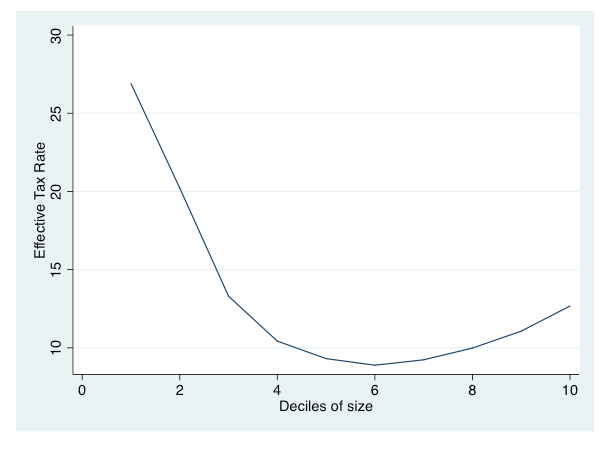

The panel then turned to business taxation, presenting new research from Ethiopia. Using data from corporate tax returns over eight years, the researchers were able to calculate the effective tax rates of different sizes of firms. What they found was that small firms bear the highest tax burden in proportion to their income, while large firms pay more that middle-sized firms (See graph below). This is because small firms do not have the capacity to fully exploit the tax system (by claiming deductions, for example), while larger firms do. However, the largest firms cannot avoid or evade as much as medium-sized firms because they face a higher degree of scrutiny and are concerned for their reputations.

Because corporations in Ethiopia are taxed at a flat rate of 30%, the graph above should look very different- the line should be more flat, rather than a U-shape. This research demonstrates that in practice, corporate taxation is not as equitable as it might seem to be on the books, and this also undermines the fiscal contract.

What does a governance-focused tax reform agenda look like?

It is by no means given that greater tax collection will lead to increased government responsiveness and accountability. In order for taxation to lead to better governance, four main strategies are required:

1. Enhance the political salience of taxes

Citizens are only able to demand reciprocity in exchange for paying taxes if they are aware of the taxes they pay. Often, they are not fully aware, as many citizens primarily pay indirect taxes that are hidden in the price of goods. The political salience of taxes can be strengthened by raising awareness of existing taxes through civil society and the media and increasing direct taxes, such as property taxes.

2. Pursue consistency in tax enforcement

When some people or businesses pay and others do not, the system is unjust, and the primary incentive for many is to individually try to avoid taxes rather than collectively demanding reciprocity from the government. On the other hand, if taxes are enforced consistently among all taxpayers, this shifts the incentives towards working collectively to seek government responsiveness and accountability.

3. Increase transparency in revenue collection and budgeting

Taxpayers are more likely and better able to make demands on government when they have access to information about how much revenue is collected and how it is spent. Therefore, ensuring this information is available and accessible is crucial for taxation to lead to better governance.

4. Support popular engagement in public finance

Finally, supporting civil society, the media, and business associations to engage with tax issues is key in fostering tax bargaining. Creating inclusive institutional spaces where this process of negotiation can take place is also important.

If you are interested in learning more about these issues, check out the ICTD Summary Brief “What have we learned about taxation, state building and accountability?” and Wilson Prichard’s book “Taxation, Responsiveness and Accountability in sub-Saharan Africa: The Dynamics of Tax Bargaining”.