In June 2021, eight Senegalese tax agents based in the fiscal centre of Pikine, the country’s second largest city, generated over 500 detailed property tax information sheets in just four weeks. The information sheets contained GIS coordinates, cadastral identifiers, property characteristics, rental value, owner identification details and even pictures.

These information sheets starkly contrast with the stacks of handwritten information sheets that could stay piled up for several weeks or even months, waiting to be manually reviewed one-by-one by already busy tax inspectors in previous property tax census operations.

The ongoing property tax census is being conducted thanks to a new property tax management software developed collaboratively by the Senegalese tax administration, our research team, and a local software developer, Groupe Idyal.

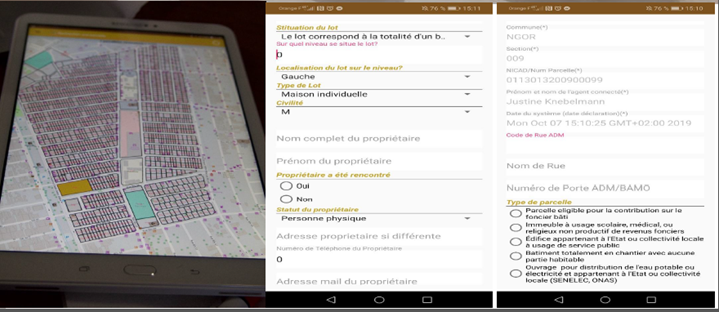

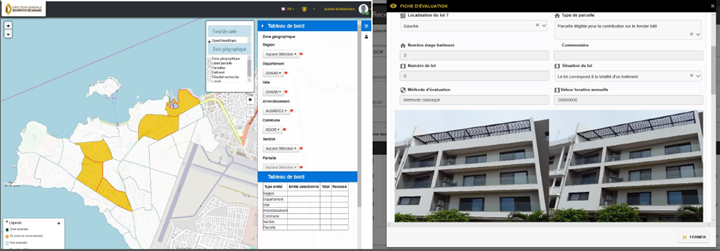

The new software includes an Android component enabling data collection in the field using tablets, and a web component allowing for information validation and editing of property tax and garbage tax notifications.

Setting up the collaboration with a local IT developer

In the context of our research team’s partnership with the Senegalese national tax administration aiming to experimentally evaluate a new property tax system in the region of Dakar, priority was given to select a local IT firm, which could work hand in hand with the tax administration over the long term, and to request that all the source code (the code written by the developers to assemble the Android and web components of the application) would be shared with the administration, so as to avoid any “lock in” that could be detrimental to the administration.

Indeed, a few years before the start of this project, the Senegalese tax administration had contracted a foreign company to develop an application with similar objectives. However, after a 2012 reform that introduced a national system for unique cadastral identifiers, the application could not be updated to include this key feature without seeking a costly new contract with the foreign company. The application also could not be easily adjusted to reflect changes in tax legislation. To avoid this situation, the new application allows the administrator to adjust tax rates and valuation methods for potential changes in the future.

The development process was carried out as a collaboration between the research team, the tax administration and the developer (initial funding for the project came from Economic Development and Institutions, while the development process received long-term support from the ICTD).

Work sessions were organised on a regular basis, bringing together practitioners from the administration, the developers, and the research team to agree on the detailed functionalities to be enabled by the software. The variables of the census forms were directly inspired by the wording from pre-existing paper sheets, which were already familiar to the practitioners. Also, whereas previously different fiscal centres each had their own habits, the exact steps for the processes of property identification, registration and taxation were harmonised so that the software could function in the same way across the country.

As soon as the first versions of the application were made available, an intensive back and forth testing protocol was set up. Importantly, tax administration staff were involved in the testing very early on. Practice sessions in the office and in the field were carried out with a small number of practitioners from several fiscal centres of the region of Dakar, during which the research team would collect comments, suggestions, and list bugs that had been detected. This is key for making adoption of the new digital tool a success.

Figure 1: The Android component allows to conduct property tax census activities using a tablet, with pre-loaded cadastral information (left). For each property, the application allows to enter property, owner and rent information (right).

Software functionalities

The software allows a property tax census to be conducted in the field based on cadastral information, to collect both data and pictures (Android application), and to compute tax liabilities, manage the taxpayer database, and produce tax notifications with detailed geolocalised information (see Figure 1).

The harmonisation of address information and the addition of GIS coordinates and cadastral identifiers to each property tax bill is a key improvement made possible thanks the digital system. Previously, our estimates indicated that around 30 percent of tax notifications were considered invalid by treasury agents because the address information did not allow the identification of the property.

Key lessons:

Our work has resulted in several key lessons that are useful to understand for those who are undertaking similar projects.

- Developing and specifying the process takes time: Defining a modernised property taxation protocol, validated by the different departments involved, and which is clear enough to be translated into software takes a substantial amount of time. In our case, over a dozen of half-day cross-department work sessions proved necessary. Our lesson was that it would be more beneficial to significantly advance this stage of the project, before even starting to contract and work with the software developer.

- Employ one or two full time product managers: Involving at least one full-time project manager in the software development process will allow to better streamline the development of the project. For instance, a practitioner within the tax administration, and an additional member of the research team conducted all the back-and-forth work between the software developer and the administration throughout the life cycle of the development.

- Inclusive testing at all stages of the development: We found that it was extremely beneficial to allow practitioners from all departments involved in property taxation to have regular opportunities to test the software and provide feedback. This facilitated the adoption of the software and its utilisation once it became functional.

- Partnership with private-sector developers: Working with a local IT company has had strong advantages, for instance, knowledge of the context, proximity to the administration’s offices allowing daily meetings, strong motivation to provide a high quality product to the government as a way to secure future collaborations — but also some drawbacks. At several points in time, the firm faced strong liquidity constraints due to delayed payments by other clients, forcing it to pause the development. Our lesson learnt here would be to pin down timing issues, consequences of delays, and obligations of the client (e.g., agreeing on a template for feedback from testing) more precisely in the initial contracts.

Figure 2: Illustration of the Web component of the newly developed software for property tax management. The web component allows to manage census activities by assigning geographic areas to field agents (left), and finally, to validate the information collected in the field and produce the associated tax notifications (right).

Digitisation is key for property tax reforms

Digitisation is with no doubt the way to go for administrations wishing to reap the fruits of property taxation, especially in contexts where cadastral, address and property titling systems are incomplete, as is the case in the vast majority of cities on the African continent.

However, switching to digital processes requires upfront investments, not only under the form of funding but also skills and time of the workforce, as such the benefits in terms of tax revenue might only materialise after the first year(s).

For this reason in some contexts it might make more sense for the administration or local government to start by digitising one aspect of the process, before moving to a more ambitious reform programme.

To learn more, read this ICTD brief about strengthening IT Systems for property tax reform.