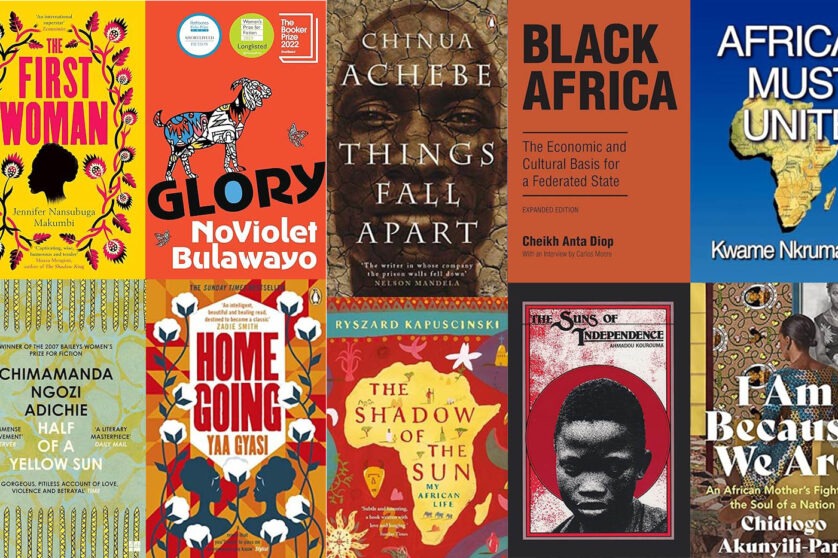

Throughout the year ICTD team members have been curating monthly reading lists with thought-provoking books covering a wide range of themes from development to politics, race, gender, occupation and even fiction. We have compiled these for you below.

Adrienne Lees recommends:

The First Woman by Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi (Uganda)

Set in the brutality of Idi Amin’s Uganda, this tale about power and gender roles follows a witty and charming central character discovering her place in the world, weaving together Ugandan folklore and modern feminism.

Glory by NoViolet Bulawayo (Zimbabwe)

An African retelling of Animal Farm, chronicling the unexpected fall of Old Horse and the comedic, farcical attempts of the animal population to initiate a true revolution. Wonderfully illustrates the absurdity of autocratic regimes.

Half of a Yellow Sun by Chamamanda Ngozi Adichie (Nigeria)

An epic novel following the lives of three characters caught up in the chaos of Biafra’s struggle for independence from Nigeria in the 1960s, and the ways love complicates ethnic alliances, class, and race.

Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi (Ghana)

An expansive story spanning seven generations, starting with two half-sisters and two very different destinies, taking the reader through the Gold Coast’s slave trade, to plantations in the American south.

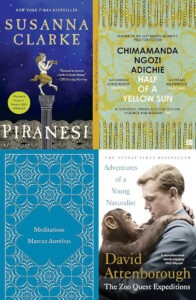

Amy Warmington recommends:

Piranesi by Susanna Clarke

I accidently read this novel thinking it was something else and I think knowing nothing was the best way to discover it. The review on Track of Words describes my sentiment perfectly: ‘Piranesi is beautifully written but unconventional and difficult to describe, the sort of book that plunges you straight into the deep end of a fully-formed world with its own unique rules, systems, style and terminology, which only reveals its secrets slowly and carefully as you dig beneath the surface.’

Meditations by Marcus Aurelius (translated with notes by Martin Hammond)

A series of personal writings by Marcus Aurelius, Roman Emperor from AD 161 to 180, recording his private notes to himself and ideas on Stoic philosophy. I enjoy dipping in and out of this, rather than a front-to-back read, it’s amazing how much his musings remain relevant in the modern day.

Adventures of a Young Naturalist by David Attenborough

A compilation of three books Attenborough wrote about the very beginning of his career. As an Attenborough fan, it was an enjoyable read following sometimes haphazard and reckless travels across South America and Indonesia in the 1950’s in search of elusive species. ‘A great book for anyone who wants to vicariously travel like an old-fashioned adventurer and seeks to understand how far we have come in developing a protective attitude to wildlife,’ New York Times.

Awa Diouf recommends:

Black Africa: The Economic and Cultural Basis for a Federated State by Cheikh Anta Diop

Black Africa: The Economic and Cultural Basis for a Federated State by Cheikh Anta Diop

This book is a continuation of Diop’s campaign for the political and economic unification of the nations of black Africa.

Africa Must Unite by Kwame Nkrumah

By a great PanAfricanist leader, sets out the case for the total liberation and unification of Africa. It is essential reading for all interested in world socio-economic developmental processes.

The Suns of Independence by Ahmadou Kourouma

Considered a masterpiece of modern African literature, enables the reader to gain unique insight into African culture and conflicts.

I Am Because We Are: An African Mother’s Fight for the Soul of a Nation by Chidiogo Akunyili-Parr

In this innovative and intimate memoir, a daughter tells the story of her mother, a pan-African hero who faced down misogyny and battled corruption in Nigeria.

Camille Barras recommends:

Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe (1958)

This is the first part of the “African Trilogy” and the author’s debut novel. Set in pre-colonial Ibgoland (in modern-day Nigeria) in the late 19th century, this powerful story features the life of Okonkwo, a clan leader, and the upheaval of local power dynamics and identity provoked by the arrival of European missionaries and colonial forces.

So Long a Letter by Mariama Ba (1980)

Another classic, which narrates the story of Senegalese schoolteacher Ramatoulaye Fall as she writes to her life-long friend Aissatou after the sudden death of Ramatoulaye’s estranged husband. This semi-autobiographical account offers a fine depiction of the women’s condition in a society that allows polygyny. Thanks to ICTD colleague Marie-Reine Mukazayire who had initially recommended it!

The Shadow of the Sun by Ryszard Kapuściński (1998)

A travel memoire written by the first African correspondent of Poland’s state newspaper, it reads like the most gripping fiction books. Filled with both historic details and personal anecdotes from the journalist’s crisscrossing of the continent and encounters with all social classes, from ministers to peasants, it provides fascinating insights into the immediate independence period and decades that follow (and the not so remote time where travelling without Internet was much more adventurous).

One Hundred Days the debut novel by writer and playwright Lukas Bärfuss (2008)

The unfolding genocide in Rwanda is told from the perspective of a young and naïve Swiss development worker and is an unvarnished account of the ambiguous role of his development agency in the lead-up to 1994 – and a thought-provoking book about the aid sector more generally.

Emilie Wilson recommends:

Poverty Safari: Understanding the Anger of Britain’s Underclass by Darren McGarvey (2017)

Poverty Safari: Understanding the Anger of Britain’s Underclass by Darren McGarvey (2017)

If you found yourself asking “why Brexit?”, “why the anti-immigration riots?”, “why the huge rise in knife crime?”, I recommend this book. If you are interested in the pernicious impact of deprivation, poverty and systematic exclusion over generations of lives, I recommend this book. Darren McGarvey (also known as rapper Loki) eloquently if grimly depicts the abject fear and volatility of his childhood in Glasgow, living in poverty. It will not be an easy read but it helps that McGarvey’s provocations are beautifully written, maybe the reason why his book won the Orwell prize.

Eugenie Ribault, IDS PhD student, recommends:

Chanson douce (Lullaby) by Leila Slimani

Chanson douce (Lullaby) by Leila Slimani

A story that can be read in one sitting. What is fascinating about this book is the violence of the main character, the babysitter, who we would have imagined to be kind and sweet, but who turns out to be quite the opposite.

Le Quai de Ouistreham (The night cleaner) by Florence Aubenas

An investigation into the working conditions of cleaners on the ferries between England and France (Portsmouth to Caen). The journalist spent six months in the shoes of a precarious worker in the north of France and explains how the economic system does not provide a decent income to live on, even if you have several jobs.

Marie Curie et ses filles (Marie Curie and her daughters) by Claudine Monteil

A biography presenting the lives of three extraordinary women who achieved outstanding professional success, including winning two Nobel Prizes for chemistry and becoming one of France’s first female diplomats. Beyond their careers, their lifestyles contrast with the times in which they lived.

Even Silence Has An End by Ingrid Bettancourt

Recounts the 6 years that the former Colombian presidential candidate spent in FARC captivity in the jungle. She describes the inhumane living conditions, her survival techniques and, above all, the social relations within the isolated camps.

Frederik Heitmüller recommends:

Senghor, sa nègre attitude by Ibou Fall (2021)

Senghor, sa nègre attitude by Ibou Fall (2021)

A political history of Senegal centered around the personage of president Léopold Sédar Senghor, who governed the country from 1960 and 1980 and whose legacy is still important today. The book not only provides tons of interesting historical facts and observations key to understanding contemporary Senegalese politics but, coming from the plume of a journalist specialized in satire, is also great fun to read.

Les bouts de bois de Dieu by Ousmane Sembène (1960)

Through narrating the story of a strike of railway workers on the Dakar-Bamako line, the author focusses on the struggle between colonized and colonizers, while engaging with other themes such as the role of women and religious leaders within colonial society, and the relationship between humans and machines.

The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity by David Graber and David Wengrow (2021)

Contrasting archaeological evidence with ideas about ancient civilizations espoused in political writing, the authors refute two ideas often found in the latter: that “development” is a linear process and that the agriculture revolution led societies into a “trap” of social inequality. Instead, the authors present a wealth of case studies which highlight a diversity of political institutions likely to have existed among different ancient civilizations.

The Rainbow Troops by Andrea Hirata (2005)

Based on his own experience, the author paints a very rich picture life in a remote village on the Indonesian island of Belitong, by telling the story of a group of students in their fight to gain access to education in the hope for a better life.

Graeme Stewart-Wilson recommends:

Waiting for the Wild Beasts to Vote by Ahmadou Kourouma

Waiting for the Wild Beasts to Vote by Ahmadou Kourouma

In this bitingly funny and savage dream-like satire, Kourouma weaves the tale of an inspired-by-real-life fictional dictator of a West African nation. The tale, recounted in the form of a panegyric, melds magic and history to tell a story of Africa from colonialism, through the Cold War, to the Western powers’ cynical demands for electoral democracy.

States at Work: Dynamics of African Bureaucracies by Thomas Bierschenk and Jean-Pierre Olivier de Sardan (eds.)

This collection of ethnographies focuses on the mundane day-to-day practices of civil servants in Africa, and through that lens challenges ideal-type images of the African state to provide a more “real” and grounded understanding of the politics of reform.

Walking the Bowl: A True Story of Murder and Survival Among the Street Children of Lusaka by Chris Lockhart and Daniel Mulilo Chama

This devastating and poignant real-life account of street children in Lusaka sheds light on the rules that shape the lives of children living on the periphery of Africa’s rapidly growing cities, and the spaces for hope and solidarity that can sometimes open.

Getting to Zero: A Doctor and a Diplomat on the Ebola Frontline by Sinead Walsh and Oliver Johnson

In this compelling insider’s account of the 2014-16 Ebola outbreak in Sierra Leone the authors capture the complexity of local and international political wrangling, while highlighting the crucial importance of individual agency in responding to the horror and uncertainty of a global health crisis spiralling out of control.

Max Gallien recommends:

Dear Committee Members by Julie Schumacher

Dear Committee Members by Julie Schumacher

Told entirely through a series of increasingly unhinged letters of recommendation by a beleaguered professor of creative writing at an American University, this is a funny send up of the type of university life that is increasingly crowded out by marketisation and managerialism, and an ode to the small spaces of humanity that can hold out in the cracks of institutional structures and fumigated literature departments.

Brand New Ancients by Kae Tempest

Originally a spoken word performance, a fast, rhythmic and vivid story of gods and men, told with the symbolism of Greek myths and the imagery of today’s world (before the rise of 5 different streaming shows about modern day greek gods). Kae Tempest’s music, rap, spoken word and poetry are all in their own way overwhelming, an assault of earnestness and rhythm and instinct all pulled together by empathy – this was one of their first pieces, and is still my favourite.

A Place of Greater Safety by Hilary Mantel

The story of the French revolution told through the relationship between Danton, Desmoulins and Robespierre, their relationships, ambitions, paranoias. An old tale that reads as inherently modern, both in its prose and in the way it gets up and close with its illustrious characters. Great for everyone who loved Wolf Hall, and for everyone who’s been scared off by its scope or its focus on Tudor England.

Measuring the World by Daniel Kehlmann

This was a huge hit in Germany in the early 2000s and has remained one of the most read books – perhaps surprisingly, as it spends quite a lot of its pages poking fun at what the country sees as its intellectual history and heritage. Telling the stories of Alexander von Humboldt and Carl Friedrich Gauss, it ponders the relationship between science and power, whether we have to see the world to measure it, and whether one of the founders of empirical geography engaged in cannibalism. It’s criminal that Kehlmann is not read more outside of Germany.

Meeko Angela Camba recommends:

Some People Need Killing: A Memoir of Murder in the Philippines by Patricia Evangelista (2023)

Some People Need Killing: A Memoir of Murder in the Philippines by Patricia Evangelista (2023)

This book documents the tens of thousands of killings that occurred in the Philippines in the name of the drug war under the presidency Rodrigo Duterte, through the eyes of trauma journalist Patricia Evangelista. While it is not an easy read (not because of the prose – it’s excellently written!), it’s an extremely important one as it does not only talk about the brutality and tragedy of these killings but provides insight as to how they happened (and continue to happen) in the oldest democracy in Southeast Asia.

Stephanie Alkoussa recommends:

Returning to Haifa by Ghassan Kanafani (1970)

Returning to Haifa by Ghassan Kanafani (1970)

This novella by Palestinian author Ghassan Kanafani is his last work before his assassination in 1972. In it, he narrates the story of Said and Safiyya who were forced in 1948 to flee their home during the Nakba, leaving behind their newborn son Khaldun. It is not until 1967 that the couple is able to return but to find someone else living in their home. The novel showcases a tragic history depicting occupation and injustice, and translates the author’s yearn for his homeland from which he was exiled. According to the Guardian, it is a “call for reciprocal awareness and acknowledgement of past injustice [which] seems more necessary than ever.”