From October 19th to 28th, the 23rd Session of the United Nations Committee of Experts on International Cooperation in Tax Matters (‘the UN Tax Committee’) is taking place. It is the first meeting of the committee’s new membership, at which those members will determine the plan of work for their four-year term.

A per usual, a draft agenda was drawn up by the Secretariat of the UN Tax Committee with matters for possible further work suggested by the previous membership. For the first time, the Secretariat also invited interested stakeholders to provide public comments in order to keep the work practical and relevant in particular to developing countries.

In our own stakeholder submission (based on an ICTD working paper), we brought a number of issues to the Committee’s attention, including the taxation of maritime shipping income and the need for the Committee to revisit Article 8 (Alternative B) of the UN’s Model tax treaty.

The old consensus of exclusive residence state taxation: outdated and unbalanced

Since the inception of the current international tax regime by the League of Nations in the 1920s, there has been a remarkably stable consensus in the international tax community that the profits generated by this trillion-dollar business are taxable not in the port states – the ‘source’ states – but where the ownership of the vessels is located, i.e. the ‘residence’ state. This consensus is reflected in Article 8 of the OECD’s Model tax convention, as well as in Article 8 (Alternative A) of the UN Model. Today, a rule modelled to these provisions is a standard feature of nearly all bilateral tax treaties currently in force.

The 1920s decision was based on two justifications. First, it was in line with the historic tradition of states to grant reciprocal exemption of profits generated in local ports by non-resident shipping enterprises resident in the other country. Second, and more important, the Technical Experts of the League of Nations believed that it would be too difficult to apportion profits, particularly in case of companies operating in several countries.

The UN Model’s impractical source taxation alternative: Article 8B

This solution makes perfect sense in a case of equal sized mercantile fleets and equal flows of shipping traffic. In reality, the bulk of mercantile vessel ownership has always been located in a handful of developed countries. In addition, in recent decades, the largest flows of maritime shipping transport involve the shipping of goods to and from developing countries, which do not have substantial mercantile fleets.

Concerns about this very one-sided revenue sacrifice for the sake of an ‘efficient’ allocation rule led the drafters of the original UN Model in 1980 to come up with an alternative, found in Article 8 (Alternative B) of the UN Model (‘Article 8B’). It essentially provides for shared taxing rights on shipping income, allowing the source state to tax non-resident shipping profits if the shipping activities taking place there are more than casual.

From its first appearance in the UN Model, Article 8B has been considered impractical due to the lack of guidance on core issues, like rules on profit attribution to the source state. However, many countries have such rules in place in their domestic tax systems. These rules only come into place in the rare instance when non-resident shipping profits are derived by a shipping enterprise located in a country with which no treaty is in place, or because a treaty is in place that incorporates a provision modelled to Article 8B. The recent termination of the shipping tax treaty between the United States and Hong Kong – two major shipowner nations – is a case in point to illustrate that even ardent residence states have rules in place to tax non-resident shipping income at source, if necessary.

The tide is rising: Reasons to update Article 8B

There are several reasons the UN Tax Committee should, after four decades, revisit and reinforce Alternative B. First, tax competition among shipowner states has drastically driven down the shipping industry’s effective tax rate. All major ship owning states have gone defensive and have adopted beneficial tax regimes in the form of tonnage tax systems or other incentives to avoid the relocation of fleet ownership. By the shipping industry’s own admission, this type of tax competition damages the business. Excessive tax benefits artificially increase the liquidity of shipping enterprises and thus triggers overcapacity, which makes it difficult for the business to generate stable profits. While not considered a harmful tax practice by the OECD’s Inclusive Framework on BEPS, the OECD’s International Transport Forum has recommended a re-orientation of maritime subsidy policies to stop the race to the bottom. Taxation at source could effectively make this happen.

Second, at a time when the international tax community is rethinking core principles that have allowed some multinational enterprises to drive down their effective tax rates, it is simply mind-boggling that on the one hand a country such as Switzerland – landlocked, yet with one of the largest maritime merchant fleets in the world – is contemplating a new tonnage tax regime to strengthen its attractiveness as a shipowner state, whereas source states – the states where the sea ports are situated and the business is physically carried on – are expected to exempt shipping transport from income tax. This incongruity is exacerbated by the fact that many of the negative externalities that go hand in hand with maritime shipping – not least its contribution to climate change – disproportionately affect the port states that will suffer from rising sea levels and extreme weather conditions.

Third, one of the main points of criticism of Article 8B has always been that the allocation rule cannot be implemented in treaty practice because the UN Model lacks guidance on how to define the source of income and attribute profits to countries. The latter is furthermore said to be utterly burdensome for the affected taxpayers. The lack of attribution rules is a fair point and a key issue that the upcoming membership should address. As for the compliance burden, if the international tax community agrees that it is feasible for digital enterprises without physical presence in a market country to be asked to keep track of the revenue generated in those market countries, surely international shipping companies can be requested to count the number of containers dispatched at a certain location?

A thriving tax treaty practice in South and Southeast Asia

Critics of Article 8B also like to point to the fact that the provision is rarely included in tax treaties to illustrate that source taxation of shipping income is simply bad policy. Granted, the overall inclusion of Article 8B in the global tax treaty network is lower than any other provision of the UN Model – 14% to be precise.

However, unlike other income allocation rules, article 8B applies only to a specific kind of business activity and one which is only relevant to a certain type of country, namely coastal developing countries with an underdeveloped domestic fleet that at the same time serve as an important trade destination. The provision is irrelevant for land-locked countries.

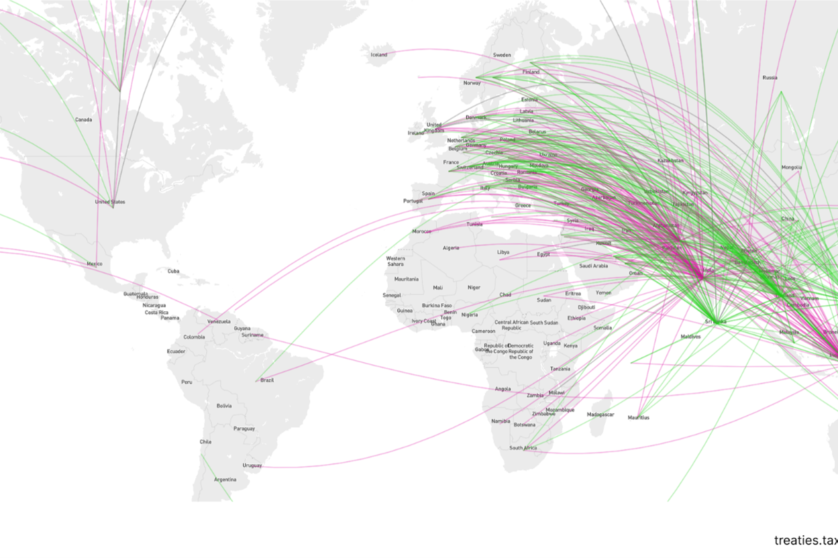

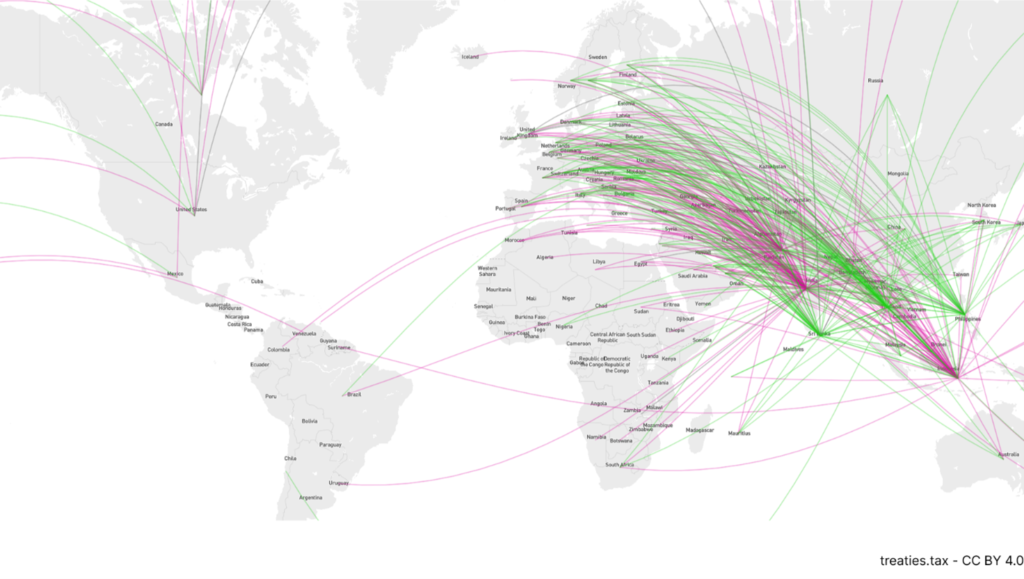

Our research shows that eight countries are responsible for 75% of all tax treaties in force that provide for source taxation of shipping profits. The eight countries – all situated in South and South East Asia – are (in alphabetical order, and with implementation rate in the countries tax treaties): Bangladesh (91%); India (17%); Indonesia (19%); Myanmar (100%); Pakistan (43%); the Philippines (100%); Sri Lanka (95%); and Thailand (86%). All of these countries subject non-resident shipping income to tax in their domestic income tax laws. And except for India and Indonesia, all of them are able to exercise these provisions in relation to the ten biggest mercantile fleet owner countries in the world, as they either have a treaty in place with an Article 8B provision or no treaty to restrict the use of domestic law. In other words, source taxation of non-resident maritime shipping income is thriving as a tax policy in the region.

Treaties in force in Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, Myanmar, Pakistan, Philippines, Si Lanka and Thailand. Treaties coloured in green allow for source taxation of shipping. Source: www.treaties.tax

An opportunity for South-South development of tax treaty policy

The Secretariat of the UN Committee has added the question ‘whether Article 8 should be fundamentally revised’ on the long list of technical issues that could potentially result in changes to the UN Model. We strongly believe it should, and our research shows that many answers can be found in South and Southeast Asian tax treaty practice. The most important issues to be addressed include the definition of source rule (including the question of whether to tax both inbound and outbound transport or only outbound), source taxation limitation, the activity threshold, profit attribution rules and the method of taxation (i.e., taxation on gross or net basis).

In fact, four of the limited number of countries with experience on the matter – India, Indonesia, Myanmar and Pakistan – are represented in the upcoming membership of UN Tax Committee and should be able to give valuable input based on their practical experience (and caution on pitfalls).

At the receiving end of the table are a number of coastal countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. Several of these (Benin, Gabon, Gambia, Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, Senegal, Togo and Uganda) have recorded their interest in the matter in the recent African Tax Administration Forum’s Model Agreement by reserving the right to tax maritime shipping profits at source. The ATAF Model incorporates Article 8 of the OECD Model which supports exclusive residence taxation of maritime shipping profits, and simply ignores Alternative B of the UN Model. To date, no other provision has triggered as many reservations by ATAF member countries. Two of these countries – Ghana and Nigeria – are also represented in the upcoming UN Tax Committee.

The issue of taxing shipping profits thus presents an excellent opportunity for South-South tax treaty policy development for which the upcoming UN Tax Committee could serve as a catalyst for change.