It is a historic moment for international trade negotiations; at the World Trade Organization’s (WTO) 13th Ministerial Conference (MC13) this month, countries are facing a crucial decision on the moratorium on Custom Duties for Electronic Transmissions (CDETs). The moratorium ensures that countries don’t apply custom duties on the online imports of digitisable products such as videogames, software, e-books, and music files. However, to remain effective this moratorium needs to be extended every two years at the WTO MC. The current moratorium, initiated in 1998, is under scrutiny, with developed economies such as the US and Japan advocating for its permanence, citing concerns about potential price increases, reduced consumption, and sluggish GDP growth if the ban is lifted. Conversely, developing countries of South Africa, India, and Indonesia are pushing for its termination. Parallelly, bans on CDETs are being incorporated in Preferential Trade Agreements (PTAs) and Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) in an effort towards setting this practice as a norm. For instance, in the FTA negotiations with Kenya, the U.S. is aiming to secure commitments against imposing customs duties on digital products.

Does the moratorium restrict the taxation of the digital economy?

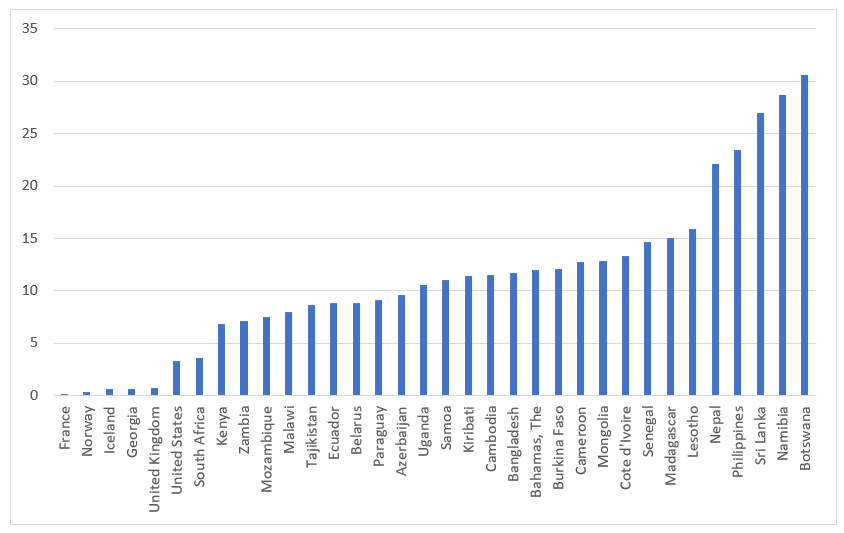

According to a new paper for the ICTD, CDETs constitute a significant revenue source for some African countries. While developed countries may experience minimal revenue losses, as custom duties form a small share of their total tax revenue, the impact is substantial for several African countries. As per World Bank data (Figure 1), the share of customs duties in total tax revenue is ten times as much in Botswana (30.6 per cent), more than triple in Bangladesh (11 per cent) and more than double in Kenya (7 per cent) compared to the US (3.4 per cent). Even with conservative estimates, developing countries are estimated to have lost USD 48 billion in tariff revenue from duty-free imports of specific ET products from 2017 to 2020. The annual estimated revenue losses for some African countries- South Africa (US$44 million), Rwanda ($14 million), and Nigeria ($1billion)- are noteworthy, underscoring the economic implications of this issue.

Source: Banga and Beyleveld (2024)

VAT versus custom duties?

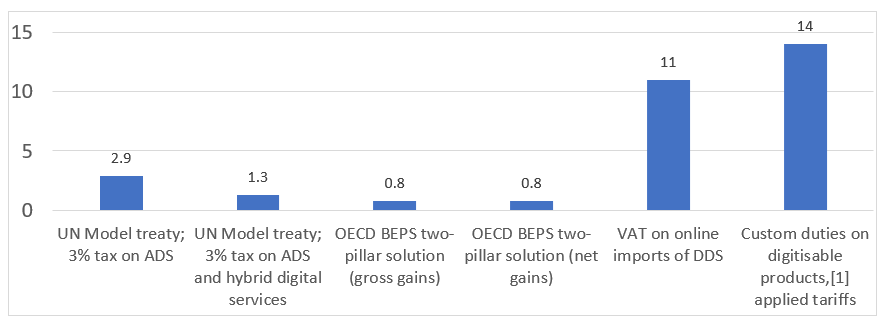

The debate extends to the choice between value-added tax (VAT) and custom duties on electronic transmissions. Developed economies suggest that developing countries can opt for VAT on digital services. Several African countries are already doing this, including Kenya (16% VAT), South Africa (15%), Zimbabwe (14.5%), Algeria (19%) and Cameroon 19.25%. It is important to note however that countries don’t have to choose between VAT and CDETs; the two are not mutually exclusive and the former can be applied while preserving policy space for applying the latter especially that for some African countries, CDETs are the most important source for revenue generation. Rwanda, for example, could gain an additional $14 million from applying customs duties, outweighing the estimated US$11 million from VAT, and outweighing revenue generated under other digital taxation approaches (Figure 2).

Source: Compiled from various studies, see Banga and Beyleveld (2024)

Note: ADS stands for Automated Digital Services

Moreover, there is a lack of clarity regarding the ‘definition’ and ‘scope’ of the moratorium. Debates centre around whether ‘electronic transmissions’ (ET) refers only to the transmission process or includes the content being transmitted. Additionally, discussions revolve around whether the moratorium covers goods, services, or both. The diverging opinions between the US and the EU on the definition of electronic transmissions underscore the complexity of the issue. The US advocates for ET to be defined as digital goods, in which case a General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) will apply. The EU, on the other hand, is pushing for ET to include all online trade services, in which cases all services delivered via mode 1 under the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) will come under the scope of the moratorium.

If all services delivered online come under the scope of the moratorium, the protection and flexibility given by developing countries to some of their domestic service sectors under the GATS may also be lost. With significant advancement of artificial intelligence and digital technologies in the last few years, many more physical goods are likely to be transmitted digitally soon. This would mean that more and more non-agricultural market access (NAMA) tariff lines will be able to circumvent duties, threatening to disregard members’ GATT and GATS schedules. For instance, South Africa has market access limitations in GATS on cross-border architectural services supply; for building plans of and over 500 sq meters, the services of a locally registered architect must be utilised. Under the broad definition of ET, the domestic markets could be completely open.

Custom duties and digital catch-up

As negotiations unfold, it is crucial to consider broader consequences of the moratorium on CDETs for domestic digital industries. Duty-free imports of ET, combined with a rapidly growing 3D printing market, will have important implications for digital industrialisation in developing countries. For example, with a permanent moratorium on CDETs, foreign automotive firms in South Africa, with large investments in 3D printing, can import duty-free computer-aided design files to 3D print auto products that have traditionally been domestically manufactured and subjected to negotiated tariffs under the GATT.

The lapsing of the moratorium will provide WTO Members with policy space to apply custom duties, with the extent of this space varying based on existing PTAs/FTAs and GATS commitments.

Ultimately, ‘policy space’ on applying custom duties on ET can allow countries to undertake more active policies to facilitate catch-up, giving them the flexibility to apply customs duties on specific imports of ET and not on others, given their own national priorities. Unlike VAT, CDETs are applied to imports of ET and therefore could serve as an important policy instrument for supporting the domestic digital industry.