Earlier this year, in June 2022, the World Bank released its latest Global Findex data on the usage of financial services around the world. The data showed that in Africa, men own and use bank accounts and mobile money accounts more than women. These gender gaps could have serious repercussions for women on several fronts, including ability to receive payment or open a business.

As Africa increasingly introduces specific taxes on digital financial services (DFS) such as mobile money (MM) – accelerating in recent years – it begs the question: Do DFS taxes exacerbate or reduce this gender inequality?

Logically, if women use DFS and MM less, then they will be less affected by taxes on DFS and MM. However, there may also be hidden gender inequalities built in the tax system, suggesting that burdens and repercussions may in fact be disproportionate for women.

Unfortunately, there is a lack of sufficient gender-disaggregated data to enable definitive studies of the underlying patterns of how men and women use mobile money differently, and changes in use due to DFS taxes. Nevertheless, we can still make an important first step by examining the rationale of DFS taxes, linking the design of these taxes to gender gaps, and thus identifying the data we will need in the future.

This blogpost focuses on links between gender gaps and – specifically – DFS taxes on transaction values. It raises critical questions requiring further research.

Gender gaps and DFS taxation: Is there a link?

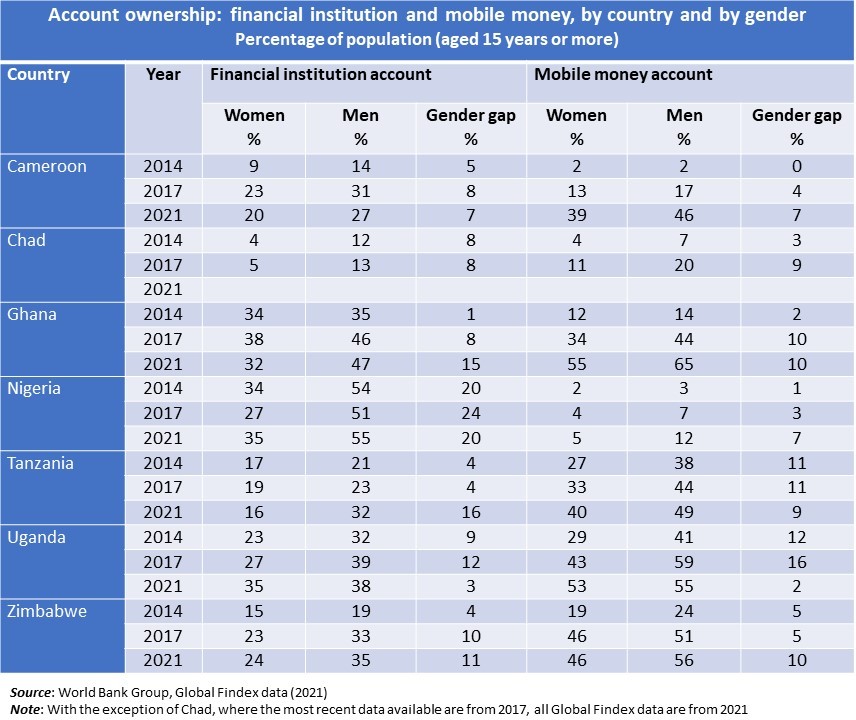

When we examine African countries that have introduced taxes on the underlying values of digital finance transactions (see table below), there are differences between men and women in owning traditional bank accounts versus mobile money accounts.

Between 2014 and 2021, the gender gap in financial account ownership widened in Ghana and Zimbabwe, but was very marginal (2%) in Cameroon and Tanzania. Other than Tanzania and Uganda, all other countries saw an increase in the gender gap in mobile money accounts.

What of DFS taxation and gender equity?

Taxes on digital finance are often seen as an attractive way to target the informal sector for tax and increase domestic revenue. However, should it be that DFS taxes disproportionately burden the informal sector, then women are likely to bear the brunt of DFS taxes because they are more likely to be self-employed. DFS taxation could place a lighter burden on men since they are more likely to be paid via other channels if they work in the formal sector.

Intriguingly, a recent study of the impact of Ghana’s e-levy on the informal sector found that men support the tax more than women, but also that men are likely to marginally pay more tax as a percentage of their income. Why are women less likely to support the tax? More research would be needed to assess gender differences in the impact of DFS tax policy for the formal and informal sector.

Is gender a factor in tax exemptions?

To answer this question, we need to know whether mobile money is used differently by men and women, and what precisely is being taxed. For instance, Ghana reduced the 1.5% electronic transfer levy downwards to 1% effective January 2023, but some transactions are exempt, including transfers for tax payments and specified merchant payments such as purchasing goods and services from shops registered with the Ghana Revenue Authority. Similarly, Zimbabwe applies a 2% intermediated money transfer tax but the tax is not payable on several transactions including payments for work or tax payments. Since men are more likely than women to own a mobile money account, and to use these accounts for digital payments, these tax exemptions could favour men more than women.

Do differences in the taxation of digital versus traditional transactions favour men over women?

In several countries, DFS taxes and taxes on banks differ. For instance, Cameroon, Chad and Tanzania apply an electronic money transfer tax, but bank transfers are exempted. Because there are significant gender differences in bank account ownership (for instance, 32% of men versus only 16% of women in Tanzania having an account with a financial institution), it seems that these exemptions benefit men more than women because men are more likely to own such financial accounts. The effect may be somewhat mitigated by the fact that women often have access to male household members’ accounts. Households often have just one account, more likely in a man’s name.

Why does Uganda buck the trend of large gender gaps?

The Findex data show a narrowing gender gap in Uganda, with a higher rise between 2017 and 2021 in the percentage of women owning mobile money accounts compared to men.

Here are the questions:

- Could the tax design, introduced and amended in 2018, play a part in the small – and reducing – gap between women and men? For instance, equal tax rates apply on fees charged by both banks and telecom providers. Uganda also applies a mobile money-specific tax on the value of the money only on withdrawals at a relatively low rate of 0.5%.

- Are women withdrawing less money than men, meaning a lower impact on women by this specific tax?

- Are women more likely to be making payments that encourage mobile money use?

The answers:

- Without a gender perspective on how mobile money is used, how the mobile money market has developed, and what the social and economic barriers to use are, we simply do not know the answers to these questions.

- Uganda’s tax has been in force for more than four years – the longest time in the countries we are comparing. The country therefore presents a unique opportunity for deeper gender research in DFS taxation.

Bridging the gender divide

To ensure DFS taxes do not inadvertently discriminate between women and men, tax policymakers should apply a gender lens in designing DFS taxes, for gender equality. It is critical to have a better understanding of the unintended consequences of DFS taxation on women and men.

Therefore, in designing a tax framework for digital finance, several gender considerations must be at the forefront:

- Understanding how women and men use DFS technologies differently, by collecting and analysing gender-disaggregated data.

- Assessing how digital finance tax policies could interact with gendered social norms, focusing on their relative impact on women.

- Examining barriers preventing women from accessing digital finance, and how relevant (tax) policies could either exacerbate or remove these barriers.

- Monitoring tax policy developments to document and address any unintended consequences of digital finance taxation.

With solid research on these questions and appropriate tax policy, women could be economically empowered through strategic and well-informed coordinated actions to address gender gaps. Such research would also enhance government efforts to fund services to reduce poverty and enhance social welfare for women and men.

The authors would like to thank Philip Mader for his valuable suggestions. This blogpost was edited by Njeri Okono.