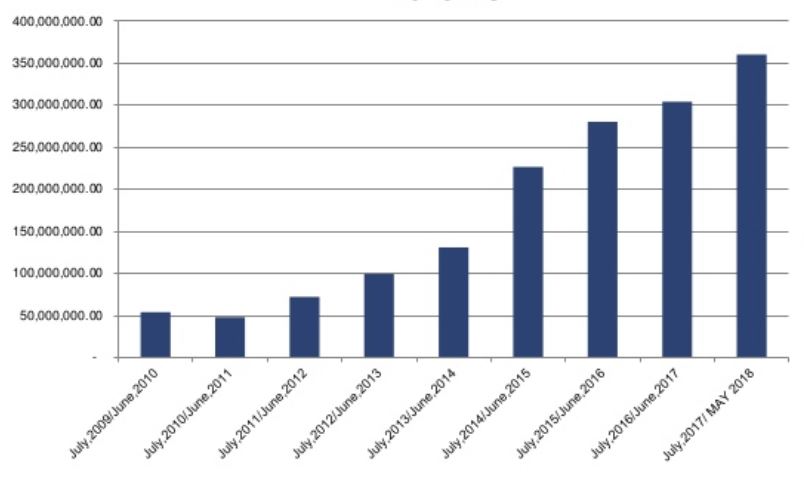

Mzuzu is the third largest city in Malawi. Before 2013, it collected very little property tax per year: K50 million ($68,000 USD) on average. However, with the implementation of the ReMoP property tax system, revenues have increased seven-fold to over 350 million in 2018, which has allowed the city to improve services including garbage collection, street lighting and road grading significantly.

The context

Prior to 2013, property tax collection was low for several reasons. First, very few properties were registered on the roll, as it had only been updated once in the previous 20 years, largely due to high valuation fees. Assessments were also irregular and inconsistent due to collusion and conflict between property owners and valuers. Poor physical addressing systems impeded the delivery of bills and the tracing of defaulters, while de facto exemptions of properties in informal settlements constrained collection, as these account for 60% of the city’s taxable base. Property valuation was costly and difficult, particularly with the lack of comparable sales data for areas where sales records are unavailable or poorly kept. Processes for delivering bills and notices were weak, and enforcement mechanisms very limited, with defaulters rarely pursued. Finally, there was a lack of sensitization as to the purpose and process of property taxation, and little confidence in the city’s ability to deliver public services with the funds.

Reform with REMOP

Addressing these challenges required a comprehensive transformational approach. Mzuzu decided to implement the Revenue Mobilisation Programme (REMOP), at first on a pilot basis. REMOP is composed of multiple phases, namely: discovery, assessment, billing, sensitization, collection, and compliance.

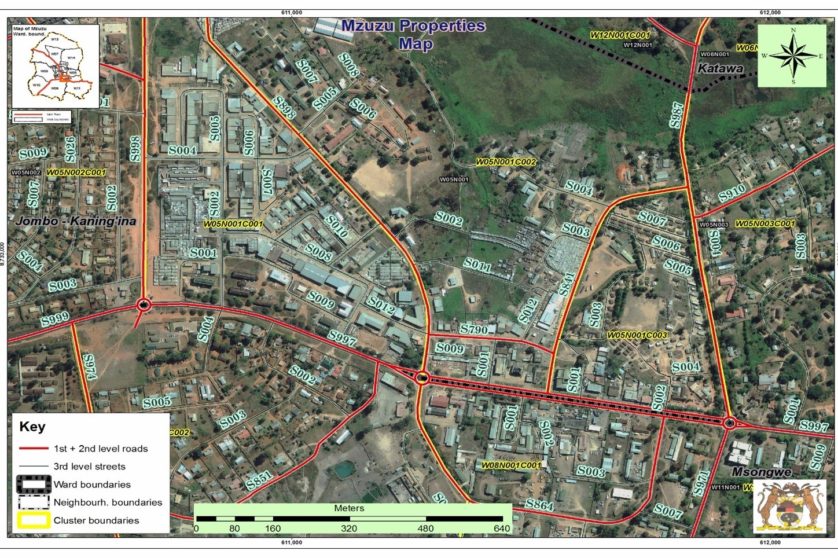

The discovery phase enabled new properties to be registered, quadrupling the number of properties on the roll from 10,000 to 40,000. It also included the introduction of a robust physical addressing system, which improved both bill and summons delivery.

The assessment phase included the introduction of area-based valuation with points (adding points for attractive features like having access to a paved road and deducting points for poor features such as lack of electricity). This system is less regressive than a purely area-based valuation, but much simpler to administer than the market-based system Mzuzu previously used. This helped the city assess many more properties, including those in informal settlements where market data is unavailable. Valuation was also made more efficient with the introduction of computer-aided mass appraisal, which city council officers found to be cost effective and easy to monitor.

Billing was made more cost-effective with the introduction of new software that allows for automatic updating of outstanding bills and printing several bills at the touch of a button. In addition, the new demand notices display all the details that influence the value of the property, making the assessment transparent. Further, the process was streamlined by billing annually rather than quarterly.

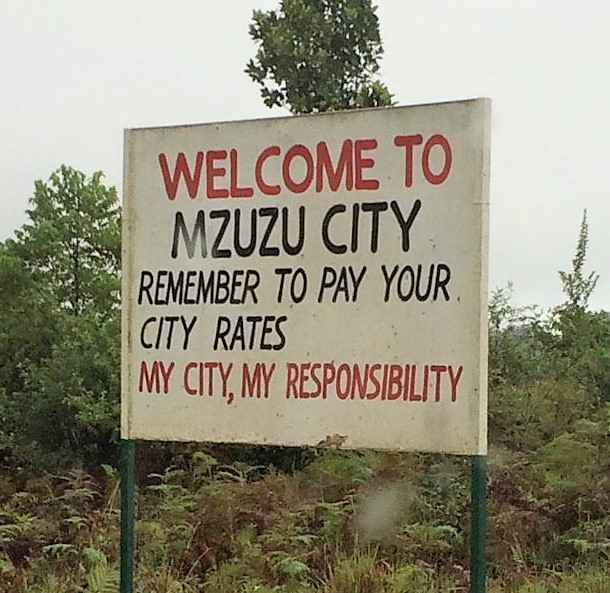

The sensitization phase involved a campaign called “My city, my responsibility,” which involved informing Mzuzu residents of the new system (including the basis of their tax liabilities and their rights and obligations), as well as the link between the tax and the benefits they could expect to see in public services. This was done via a weekly radio show and radio announcements, posters and banners, newspaper articles, and updates at ward meetings. A special information meeting was also arranged with community business leaders, as they would shoulder most of the tax burden. All this engagement was important in persuading people to pay, as the majority previously believed that the Council received funds from the central government to provide for most local infrastructure and services.

Finally, the process for tax collection was restructured, putting an end to door-to-door collection and introducing payments via banks. This reduced cases of pilferage and increased taxpayers’ trust in the system. Mzuzu also encouraged a bank to open a branch at the Civic Centre, which made payments to the council convenient and allows transactions to be recorded directly with the city administration.

Finally, the process for tax collection was restructured, putting an end to door-to-door collection and introducing payments via banks. This reduced cases of pilferage and increased taxpayers’ trust in the system. Mzuzu also encouraged a bank to open a branch at the Civic Centre, which made payments to the council convenient and allows transactions to be recorded directly with the city administration.

In terms of ensuring compliance, issuing summons to defaulters was introduced with letters prepared by a lawyer and delivered by the city. This yielded positive results, as those summoned pay to avoid the embarrassment of going to a court hearing.

The challenges

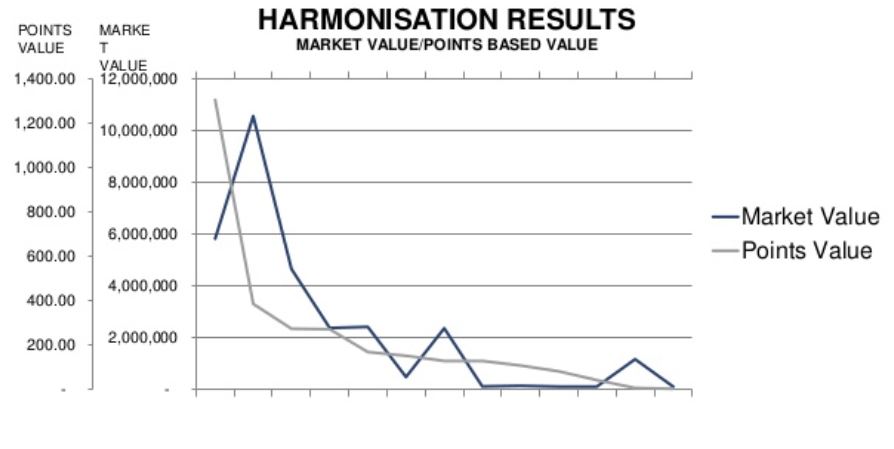

Although the reform has achieved significant success, there were two problematic regulatory and legislative issues. First, the points-based valuation method is not provided for under section 68 of the Local Government Act (1998), which specifies for market valuation. Second, section 67 of the Act requires valuers to be registered with the Board of Surveyors Institute of Malawi, but as the project was piloting a new approach, this necessitated using a valuer who was not registered.

In order to address these issues, the project undertook an exercise to compare market-based rates with those derived from the points-based method: 50 properties of various types were evaluated, and the results demonstrated that the points-based rates closely mimicked the market-based rates, and were progressive. Second, the project appointed a registered local valuer in consultation with the Ministry of Lands who was familiar with the local property market. While he agreed that the points-based approach produced acceptable figures, he later declined to certify the remaining properties on the roll. As such, the Council is in the uncomfortable position of using a roll that is producing positive yields, but is uncertified.

A model for African cities?

Mzuzu’s success demonstrates that the comprehensive REMOP model is well suited to developing country contexts. Where data on comparable sales in unavailable, the points-based method offers a simpler way to value properties while still obtaining progressive rates, while computer-aided mass appraisal lowers the cost of administration. The transparency of the process, as well as the emphasis on community engagement helps to enhance the social contract between citizens and local councils. With sufficient political will to overcome resistance, increased revenues from property taxation can enable councils to achieve demonstrable improvements in service delivery. In Malawi, other city councils are now consulting Mzuzu as a Centre of Excellence – perhaps other African cities could also learn from its experience.

See the practical guidance note on implementing property tax reform with the points-based valuation method here or learn more about the African Property Tax Initiative.