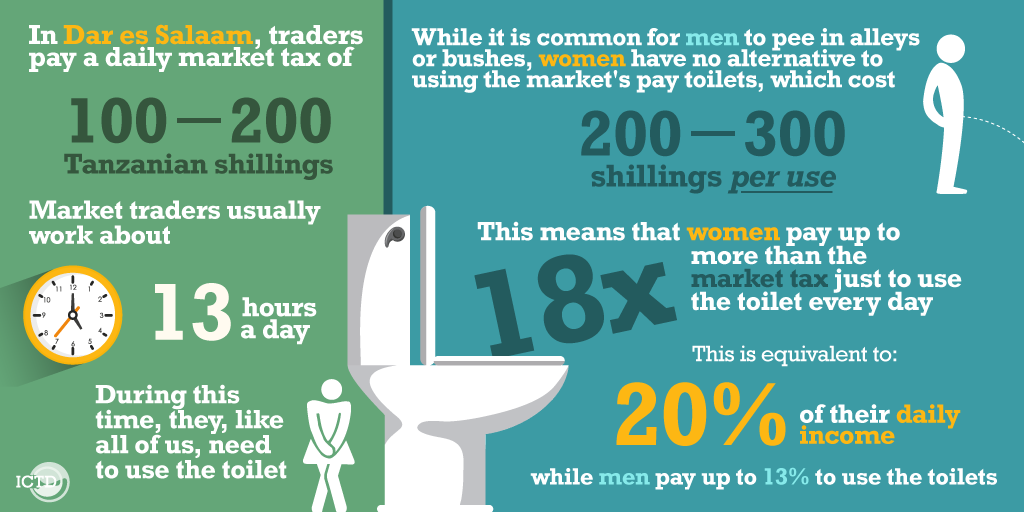

In 2018, the International Centre for Tax and Development (ICTD) published findings from a research study in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. While the researchers did not find any evidence of gender bias in the way market traders were taxed, they did find a major gender issue they did not expect – toilet fees. They found that female traders paid up to 18 times more for their daily use of toilets than they paid in market taxes – equivalent to 20% of their daily income. A subsequent study of flea markets in Zimbabwe found the same thing, with women having to pay up to $1 each time they use the toilet, when most make less than $15 per day.

The burden of these fees is significantly heavier for women because men can more easily avoid using the market toilets by peeing behind a nearby tree or building, and women need to use the toilet more often when they are menstruating or pregnant. The high costs of using the market toilets also poses health risks, as the women interviewed reported drinking and eating less to avoid having to use the facilities, which can cause dehydration, chronic constipation, and bacterial infections like urinary tract infections.

This research has not received as much attention as it deserves. But it has stayed with me. Two years ago, I presented the findings at a global conference on “Taxation and the Sustainable Development Goals” at the United Nations. Unbeknownst to my audience, a few minutes before my session began, I had to rush to a toilet because I had released a heavy flow of blood. My period had started. I realised when I reached the toilet that if I had not made it soon enough, my clothes would have been soiled. Throughout the rest of the conference, I kept popping in and out of the toilet facilities to switch one sanitary pad for another.

Does reading these details make you feel uncomfortable? Well, it makes me uncomfortable to reveal them. I would really rather keep such things to myself. But this is my reality as a woman. The reality of being a woman is that each month, I get my period. The reality of being a woman who has given birth is that my bladder is not as strong as it was before having children. The reality of being an African woman is that I am more prone to suffering from uterine fibroids, which makes my periods much heavier. All this invariably means that I need to use the toilet more often. I have a hard time imagining how much it would cost me if I had to pay to use the toilet at my workplace every time I needed one.

But, you may ask, what does this have to do with taxation? When we have presented these findings at tax conferences, the audience is always very sympathetic to the fact that something must be done. But they are also quick to insist that this is not a tax issue, and that we should not mix things like user fees up with taxes. As a result, conversations such as these are often relegated to the periphery in favour of more mainstream and institutionalised notions of taxation.

This is problematic. It represents a failure to distinguish between how fiscal systems work in high-income countries and how they work in low-income countries, particularly in Africa. Payments such as those made by market women in Tanzania are dismissed because they do not meet our idealised notion and understanding of taxation. They are not found in laws, they are not captured in budgets, and sometimes, they are not even paid to government agents.

But in most African countries, these are the types of payments that fund the provision of many public goods and services. In a study conducted in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, researchers found that the largest part of households’ overall tax burden (67% of payments) came from formal and informal user fees to access essential public services including education, water, health, and electricity. Although user fees are not taxes in a strict legal sense, when people have to pay them to access essential services that are commonly provided or at least subsidised by governments, they are critical to understanding families’ economic reality.

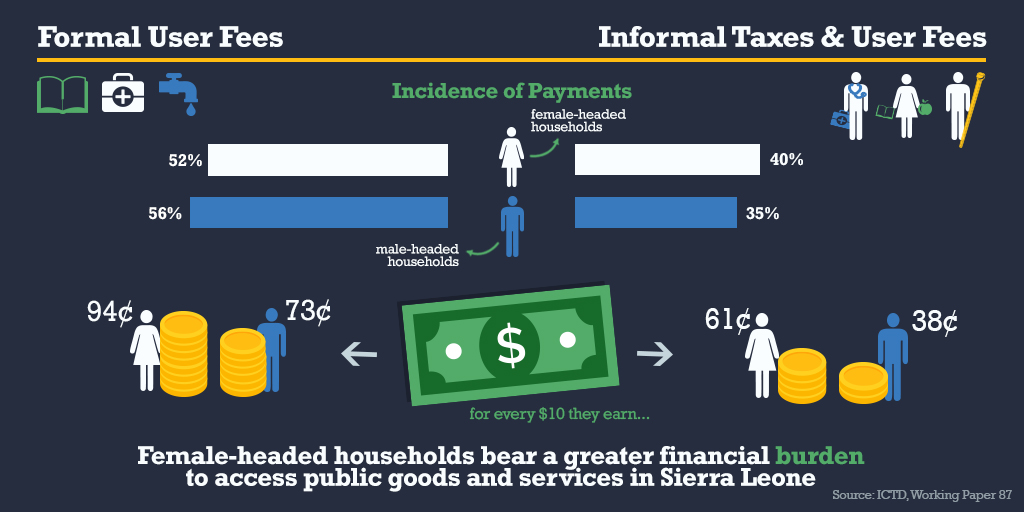

A study conducted in Sierra Leone also found that households paid more formal user fees (including school, health clinic, water, business license, and court fees) and informal taxes and user fees (payments to non-state actors like traditional chiefs, community development associations, and neighbourhood security groups, as well as informal payments to doctors and teachers) than formal taxes to the government. In addition, the researchers found that these payments make up a significantly greater portion of female-headed households’ income, compared to male-headed households.

Therefore, we cannot use the same narrow definition of taxes as in high-income countries to understand the true economic burdens of Africans, particularly women. We need to include user fees and informal payments for public goods and services in measures of people’s total tax burdens, and for policy purposes, include them in fiscal incidence analyses. This way, they will no longer be largely invisible, as they are now, but can be counted and accounted for.

Therefore, this International Women’s Day, I challenge you to dare to call these taxes.

- If you care about fair tax systems, you need to call these taxes.

- If you care about women’s health, you need to call these taxes.

- If you care about women’s dignity, you need to call these taxes.

- If you care about women having equal opportunities to participate in the economy, you need to call these taxes.

Of course, there are many obstacles to women’s empowerment in the Africa, but today, let’s start with toilet taxes.