About two years ago, the ICTD began a new research program on gender and taxation with the support of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Following a workshop with our African stakeholders in Ghana, we decided to pursue two main areas of enquiry 1) the representation of women in African tax administrations, and the impacts of their participation on tax collection and revenue authority performance, and 2) the differing impacts of taxation on men and women, and particularly how both formal and informal tax systems impact on the livelihoods of poorer African women. So, what have we learned so far?

Women are very good tax administrators

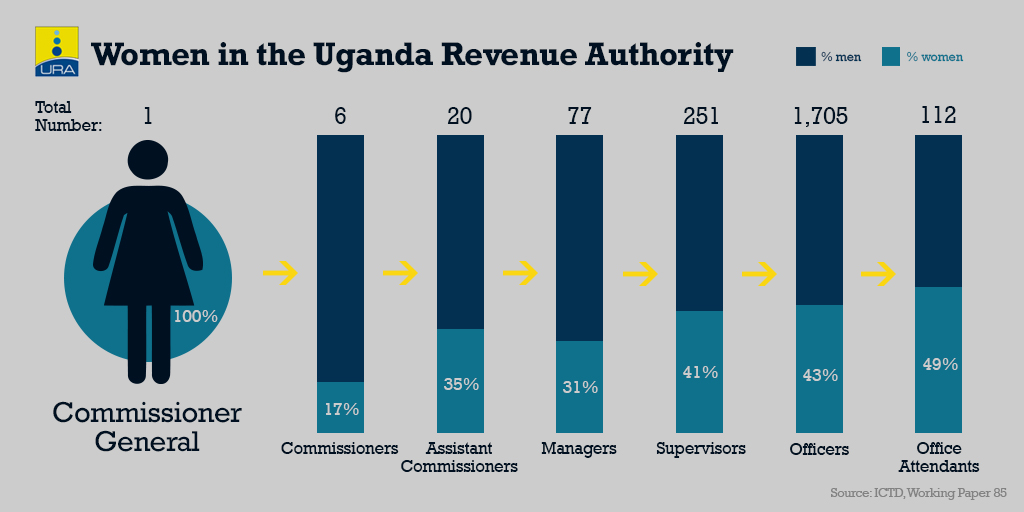

Tax administration has traditionally been a field dominated by men, but women’s participation is increasing. The Uganda Revenue Authority (URA) undertook a study to examine the representation of women across the organisation, their performance, and the perceptions of men and women of the gender dynamics in the workplace.

In terms of representation, in total, 39% of URA employees were women at the end of 2017. Women are present in significant numbers in all departments, with the least frequent being customs at 35%. A majority work in junior positions, with a few in leadership, including the Commissioner General Doris Akol. There are also regional differences, with women constituting a low proportion of staff outside the central region where Kampala, Entebbe International Airport, and the URA head office are located.

In terms of their performance, the study found that on average, women receive slightly higher scores than men on their six-monthly appraisals. They also tend to remain with the revenue administration longer than men: 12.3 years on average versus 11.6 years. Finally, male employees are more than twice as likely as women to be subject to disciplinary action (termination, suspension or dismissal).

In terms of perceptions and attitudes, women are not perceived as a novelty or a threat by their male colleagues, and both women and men seem relaxed and satisfied about working in a mixed environment. However, more men (61%) than women (23%) were satisfied with the URA’s current level of gender diversity. Overall, the case suggests employing women is beneficial for the effectiveness of tax administrations.

When we look beyond formal taxes, women face a higher fiscal burden to access public goods and services

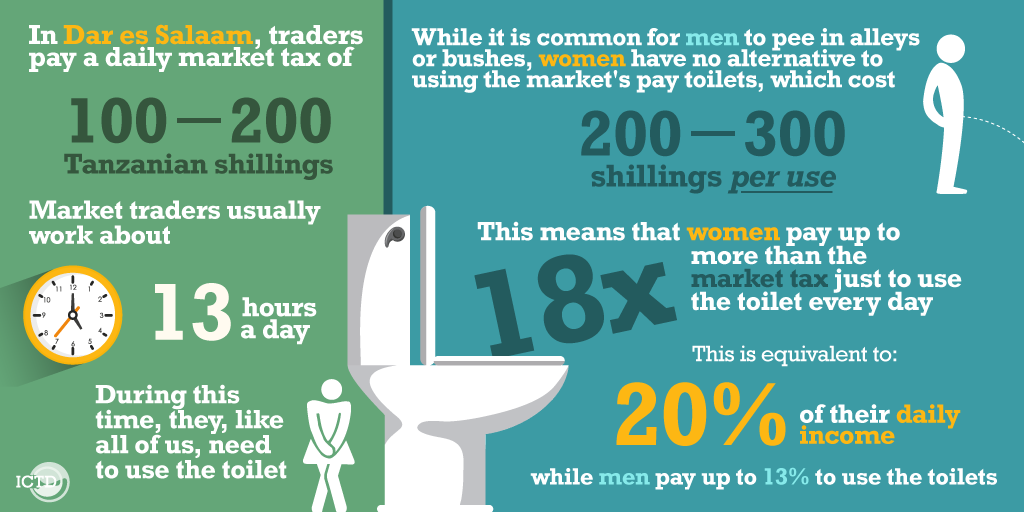

Another ICTD study examined the taxation of traders in nine city markets across Dar es Salaam. Although the researchers found no gender bias in the payment of market taxes, they found that women traders pay up to 18 times more for their daily use of the market toilets than they pay as market tax. In many cases, female traders have to pay 20 per cent of their daily income on toilet fees. This represents a major adverse impact on women traders, who require toilets more frequently than men, and have fewer alternatives.

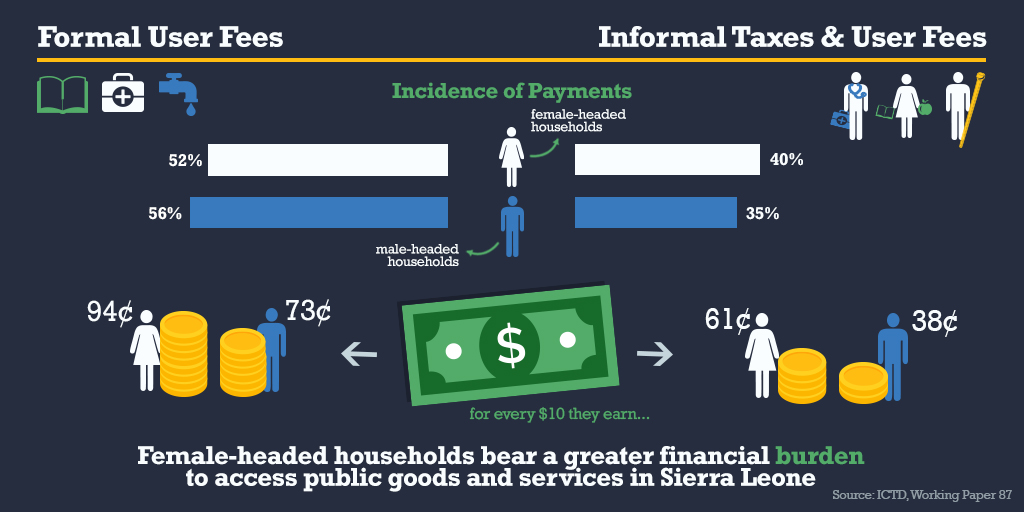

This demonstrates that a focus on formal tax systems is insufficient for revealing the gender-differentiated patterns of use and funding of collective goods and services. This is also evident in a study from Sierra Leone, which investigated the gendered differences in the payment of formal and informal taxes. The study found that although male-headed households are more likely to pay formal user fees (like school fees, health clinic fees, and burial and marriage fees), they pay a smaller amount than women in relation to their income. At the same time, female-headed households pay more informal taxes and user fees (like payments made to non-state actors like chiefs and community development associations and informal payments to doctors and teachers). The burden of these informal taxes and user fees are much higher for female-headed households, representing 61 cents of every $10 they earn, compared to 38 cents for male-headed households.

Implications for political representation and engagement with the state

The well-known slogan of the American Revolution was “no taxation without representation,” but does the logic work in the reverse; if women pay fewer formal taxes, do they miss out on political representation? In Sierra Leone, representation within the chieftaincy is based on payment of the local (poll) tax, and people hold strongly gendered views on the duty to pay this tax, with men commonly paying on behalf of female spouses and family members. This sense of different taxpaying responsibilities between men and women is rooted in colonial institutions and entrenched gender norms. Chiefdom councillors, who exclusively have the right to vote for paramount chiefs, are almost universally men, and women are excluded from the collection of local taxes and decision-making. In the infrequent cases where women have held the post of Paramount Chief, important decisions have sometimes been handled by male secret societies instead of by the female chief. Therefore, due to the embedded nature of gender discrimination in chiefdom administrations and politics, it is quite unclear that if women paid the local tax more, their representation would improve.

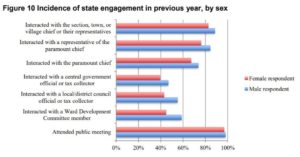

A related question is whether, because women pay more taxes through informal channels, their opportunities for engagement with the state (and corresponding opportunities to build more accountable relations) are also more limited. In Sierra Leone, women do have less contact with government and chiefdom officials at all levels (see chart). However, the reasons for this are multifaceted (including lower levels of education, multiple demands on their time, and social norms discouraging women from voicing their views in public), and so are not solely related to taxation.

Tax systems and gender equity

Last week, the IMF published a blog on women in government budgets, which argued that “taxes should not be overlooked.” Based on the ICTD’s research, we believe there is a need to go further, and that informal taxes must not be overlooked. Because things like user fees and contributions to community development are not strictly taxes, they are invisible and unaccounted for in government budgets and planning. However, they represent a significant means by which many Africans, and women in particular, procure public goods and services in the gaps left by the state. If we want to understand the real fiscal burdens borne by men and women in Africa, we must examine both formal and informal forms of taxation. As Vanessa van den Boogaard writes,

“Gender inequities are embedded within social, political, and economic structures; understanding these inequities thus requires looking at the full range of these structures, both formal and informal.”