This research was conducted alongside the ICTD/LoGRI-led initiative to implement comprehensive property tax reforms in Freetown, Sierra Leone. This reform project, implemented in partnership with the IGC, dramatically increased revenue collection and progressivity, while it was accompanied by initiatives to strengthen public service delivery, including via the implementation of a new participatory budgeting process.

Generating adequate tax revenue remains a significant challenge in most lower- and middle-income countries. With an average of 16%, the tax-to-GDP ratio in African countries is substantially lower than the 34% seen in OECD countries. In Sierra Leone, where this ratio amounts to only 12%, low tax revenues significantly constrain the government’s ability to provide essential public services and invest in development.

While high-income countries typically focus on enforcement to enhance compliance with tax policies, low-income countries often lack the resources and administrative capacity to implement such measures effectively. However, if governments are able to signal that tax revenue is used to the benefit of the people, this may incentivise individuals to pay taxes even without strict enforcement.

In a field experiment in Freetown, Sierra Leone, I inform residents of registered properties about public services delivered by the local government to make the beneficial use of tax revenues more salient to taxpayers. These services include, among other things, the provision of public toilets, water tanks and boreholes, or furniture for classrooms in public schools. My results show that property tax payments among individuals who receive such information are on average 20% higher than among individuals who do not receive any information. The messages, however, work differently for residents of lower-value properties as compared to those living in higher-value properties. I’ll explore these differences in greater detail as we move further along in the blog.

Background: In Freetown, council collects taxes for less than a quarter of registered properties

In 2020, Freetown implemented a new property tax system, registering all taxable properties and adjusting both the valuation of properties and tax rates to make the system more progressive. Within this new framework, tax bills specifying the amount of taxes to be paid are sent to property owners on an annual basis. These bills can be paid at bank branches across the city or directly at the Freetown City Council (FCC). This setup provides the government with clear information on who should pay taxes, and how much is owed. While these reforms aimed at improving both fairness and accessibility of the tax system overall, taxes are paid for only 22% of registered properties.

How can we explain this low compliance? A major reason for low levels of compliance across developing countries is the lack of effective enforcement. In Freetown, although in theory, penalties for late payments, the possibility of prosecution, and the risk of property seizure exist, these are rarely enforced in practice. Another key factor that may influence tax compliance is taxpayers’ satisfaction with public service provision. Under the leadership of the current mayor, Yvonne Aki-Sawyer, the FCC has made substantial investments in services like water access. However, while property owners in Freetown state to be more willing to pay taxes in exchange for public services, the government’s efforts do not seem to be rewarded. This suggests that either the government’s commitment is not salient enough to taxpayers, or that they are dissatisfied with the provided services.

The Experiment: Testing the Effect of Public Service Information on 5,500 property owners

To examine whether making public service provision more visible can increase tax compliance, I conducted a large-scale experiment involving nearly 5,500 property owners and tenants in Freetown. The participants were randomly divided into three groups: one-third received no additional information about public services, while the remaining two-thirds received both a phone call and an SMS informing them about services delivered by the FCC.

These messages are unique in several ways:

- Specificity: Rather than providing general statements about tax revenue use, I inform individuals about specific examples of services recently delivered by the local government.

- Verifiability: I compile a dataset of all locations at which the local government provided public services in the three years prior to the experiment. I then inform individuals about both the type and location of these services, enabling them to verify their provision.

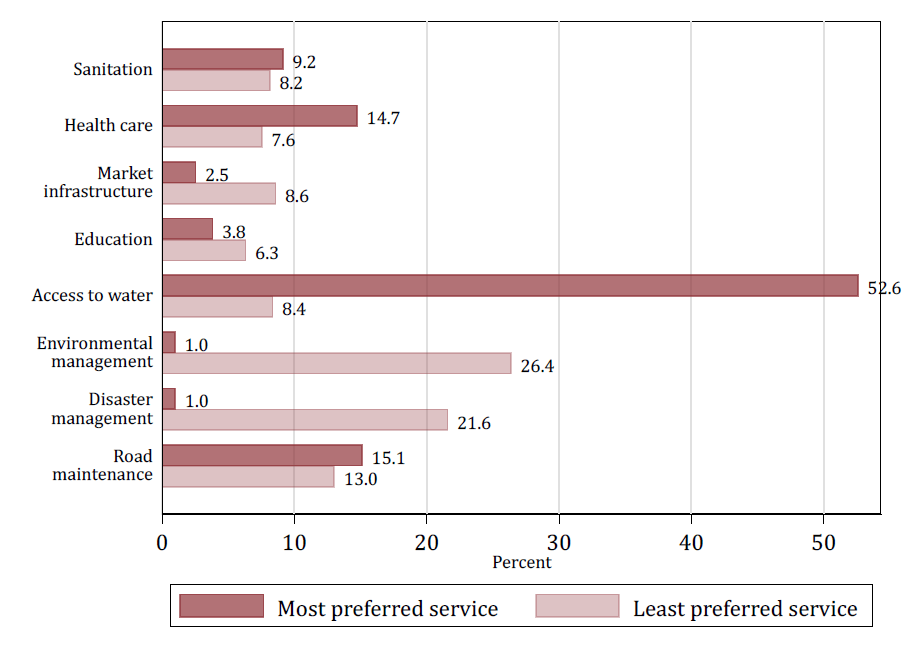

- Preference Consideration: In a baseline survey, I ask participants about their most and least preferred types of public services. To test whether preferences determine how individuals respond to public service messages, I experimentally vary whether individuals are informed about the former or the latter.

Citizens in Freetown prioritise improvements in access to water, and so does the government

Unsurprisingly, access to water emerged as the top priority for the majority of residents (Figure 1). Freetown faces severe water shortages, and only about 5% of the city’s population has access to piped water. Anecdotal evidence further suggests that up to 40% of residents living in registered properties lack any access to water. With almost 50% of the local government’s service efforts directed toward improving water access, it is clear that the FCC recognizes and is actively responding to citizens’ most urgent needs.

Information about Public Services Increases Tax Compliance

Using administrative tax payment data, I find that individuals who receive information about the provision of public services increase timely tax payments by an average of SLE 24. This amounts to approximately 7% of the average annual tax liability and represents a 20% increase compared to individuals who did not receive any information. Importantly, the intervention also proved to be cost-effective, raising up to 3.5 times its cost in additional tax revenue.

The impact of information varies depending on the extent to which individuals rely on public service provision. Residents of lower-value properties, who are more dependent on public services, are more likely to pay taxes when informed about geographically accessible services addressing their most pressing needs—in particular, water provision. While most individuals who receive information about water have indicated it as their top priority, the positive response is not limited to those with a preference for water services. Even those who do not prioritise water respond positively to information about accessible improvements in access to water, increasing their likelihood of paying taxes by up to 16 percentage points. These results suggest a benefit-based approach to taxation among residents of lower-value properties and are well aligned with their substantial need for the provision of public services.

For residents of higher-value properties, however, personal benefit seems to be less relevant. These individuals react to public service messages when they shift their priors about service provision by the local government. Learning about the government’s capacity to provide services seems to motivate them to pay substantially more taxes. Given that tax rates are higher for higher-value properties, these individuals contribute the majority of the revenue gains from the information campaign.

One may be concerned that these effects are driven by increased fear of enforcement or increased awareness about one’s tax duty rather than the salience of public service provision. However, survey data collected after the experiment suggests that there is no significant difference in the perception of the government’s enforcement capacity across groups. Individuals are also unlikely to be differentially aware of their tax duty given that awareness is mainly raised by the tax bill itself, as well as the baseline survey—which is administered to both groups of individuals. Finally, the variation in responses depending on the specific public service message suggests that the content of the message, rather than external factors, is key in influencing behaviour.

Policy implications and what to focus on next

These results highlight the potential of using information about public services to increase tax compliance and shed light on the mechanisms driving these effects. While scaling up such information campaigns may require further research, three key insights emerge:

- Preferences matter but government knowledge does too: While individual preferences for specific services play a role in tax compliance, governments may not need detailed data on these preferences to design effective information campaigns. As long as they understand the city’s most urgent needs, providing relevant information can shift taxpayers’ willingness to comply.

- Increasing compliance among residents of lower-value properties: Informing those with lower tax liabilities may not generate significant revenue, but it can expand the effective tax base by encouraging more individuals to pay. This can strengthen the government’s credibility and capacity to implement local policies.

- Perception shifts among higher-income taxpayers: Although higher-income residents may not directly benefit from the services provided, updating their beliefs about the government’s ability to deliver public services can lead to substantial increases in tax payments.

While this experiment offers valuable insights into how public service information can boost tax compliance, it also raises several open questions. For instance, how does information about services interact with enforcement efforts? Could such messages complement enforcement strategies by balancing penalties with positive information about tax revenue use? How can we incorporate information about service provision into tax systems to generate long-term effects on compliance? And how do these effects evolve as the level and quality of public service provision changes over time? These are important questions that I hope to explore in future research.

Find out more about Laura’s project and her other research here.