Developing countries lose substantial revenues every year to corporate tax avoidance, exacerbated by globalization and digitalization. As part of the OECD/G20 project on addressing the tax challenges of the digitalization of the economy, the OECD secretariat have recently presented the Unified Approach (UA) to deal with the tax revenue losses from digitalization, by giving market jurisdictions access to more tax revenue (“Pillar One”) and by effectively introducing a global minimum tax rate (“Pillar Two”).

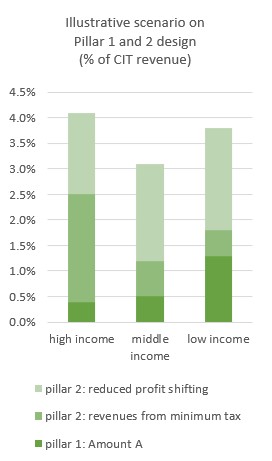

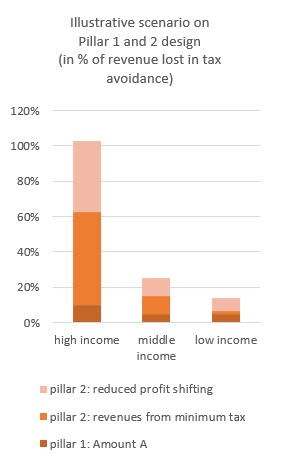

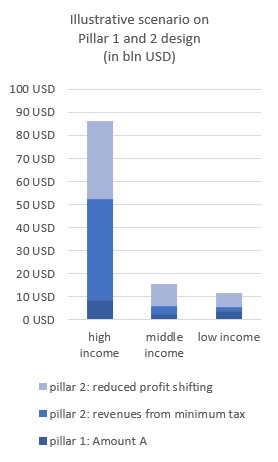

The OECD claims that the UA will produce similar revenue gains for both developing and developed economies. However, looking at the data in terms of ‘compensation’ for tax revenue lost to avoidance, or in absolute amounts, it becomes clear that the potential rewards for developing countries are quite small.

Sources: OECD Economic Analysis, OECD BEPS 11 final report, UNCTAD World Investment Report 2015 and author´s own calculations.

This begs the question: Is the UA beneficial (enough) for developing countries, or are there better options? In a recent working paper, I tried to answer this question by examining the impact of the UA proposals for developing countries, as well as exploring alternative policy options.

Assessing the impact of the Pillar One and Pillar Two proposals

Under Pillar One of the UA, Amount A proposes to introduce a method to reallocate part of the residual profit of multinational enterprises (MNEs) to jurisdictions in whose local market they operate, but where they have no physical presence. My findings show that it is unlikely that Amount A would give developing countries access to significant additional tax revenue. Based on an analysis of the profits and profit margins of ten of the world’s largest digital companies, I find that developing countries could, on average, expect about $100,000 USD in extra tax revenue per billion in reallocated (residual) profit. This reallocable profit should further be divided over eligible markets based on relevant local sales, meaning that most developing countries would get far less than larger, richer markets.

In addition, applying Amount A properly would be hugely complex and require substantial international coordination. Tax administrations would need to determine 1) which companies are in the scope, 2) how much of their profit should be reallocated, and 3) how this should be divided amongst the eligible market jurisdictions. This would likely pose a significant challenge for developing countries with limited administrative resources.

Amount B introduces a fixed remuneration for marketing and distribution activities, in order to shift more tax base towards market jurisdictions. It is conceivable that negotiations on Amount B will not result in much extra tax revenue for developing countries, as residence countries could well oppose any significant shift of the tax base to developing countries, especially in a context where the representation of developed and developing countries is unequal.

In the working paper, I estimate possible extra tax revenue for developing countries between $1.2 and 5 billion USD overall. This analysis is based on data of global corporate spending on marketing and logistics and relative GDP levels. These numbers, however, are subject to a large degree of uncertainty. A proper impact assessment requires firm-level data and transfer pricing documentation to determine 1) the amount spent on intra-group marketing and distribution services, 2) the services provided by developing countries and 3) the profit margins of these services. The OECD has not provided an impact assessment for Amount B since this data is not currently available.

In addition to outright revenue gains, developing countries might benefit from Amount B for other reasons. Developing countries currently lose revenue due to transfer mispricing as they often lack proper national transfer pricing legislation and/or the resources to argue against sophisticated transfer pricing reports by MNEs. A fixed percentage for marketing and distribution services could help strengthen the negotiating position of tax administrations (and prevent difficult and costly disputes). Furthermore, fixed percentages – even percentages comparable to current margins – could lead to an overall increase in in effective tax rates, as rates are usually higher in developing countries than in developed countries and investment hubs.

Finally, Pillar Two will likely have a larger effect on tax revenues. However, it still might leave developing countries disappointed. The reason lies in the probable design of Pillar Two. The Inclusive Framework leans towards an approach based on the so-called “income inclusion rule”. That approach is, by and large, advantageous for residence countries, as it allows for a top-up tax at the residence country level. For developing countries, however, the “undertaxed payments rule” would be preferable, as it ensures an appropriate level of taxation by disallowing certain costs to be deducted in the source country.

Alternative policy options

If there is little to gain from the Unified Approach, could developing countries do better? In the working paper, I present three alternative policy options: 1) scrap Amount A, 2) transfer administrative requirements to residence countries for the application of Amount A, and 3) consolidate relevant activities in developing countries into the residence country in exchange for a share of the consolidated tax revenue.

Clearly, option 2 and, particularly, option 3 would be quite controversial, as there would likely be concerns surrounding tax sovereignty. However, these measures would effectively free developing countries from an administrative burden that may not be feasible for them to carry. Option 3 especially could have additional positive benefits. First, it would make aggressive tax planning superfluous and would therefore curb tax avoidance. Second, it would prevent predatory tax competition between developing countries. Third, it would eliminate the need to solve possible double taxation issues through tax treaties, thus preventing future lengthy dispute resolution procedures. Finally, it might move the international tax system more towards a consolidated approach. This would do away with transfer pricing, which could truly make global profit taxation more robust, equitable, and future-proof.

A window of opportunity?

Amount B might be the best bet that developing countries have to actually get more tax revenue from the Unified Approach proposed by the OECD Secretariat. But, the end result of the negotiations could also be that even Amount B would prove to be a dud. Therefore, if developing countries do not want to be overlooked in the negotiations, they might want to present alternative policy options that would result in at least the same if not additional tax revenue, and that fit better with their administrative capacities. The US threat of withdrawing from the Pillar One discussions might give developing countries time to do that, as well as garner some support from other market jurisdictions in the Inclusive Framework. While this development makes it uncertain how discussions on Pillar One will continue and whether Pillar One and Pillar Two will still be viewed as a single package, for developing countries, the US threat might just be a blessing in disguise, helping pave the way towards a “new deal” on international tax.