Taxing transactions made via digital financial services differently from those made via traditional banking services can have unintended consequences

In recent years, several countries in Africa have introduced sector-specific taxes on transactions made via digital financial services (DFS). With these taxes, governments aim to increase domestic tax revenues and help plug budget deficits.

Some countries have specific taxes based on the value, or amount, of the DFS transaction, unlike, for example, taxes on transaction fees charged by providers to consumers or taxes on the providers themselves.

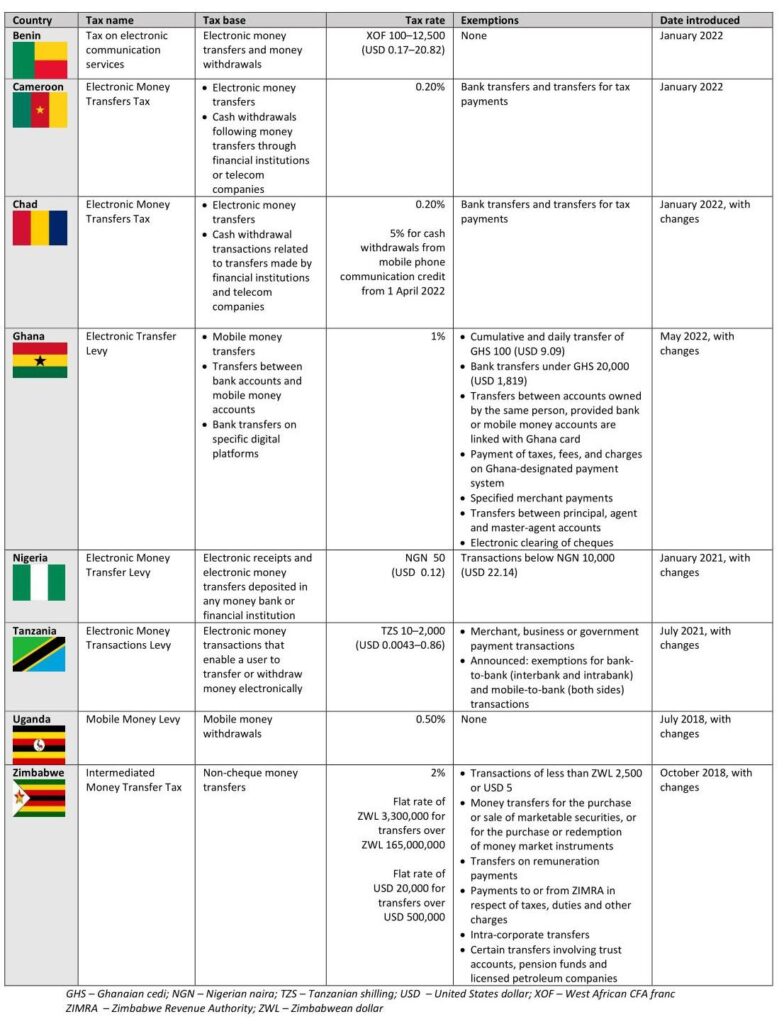

The countries with taxes on transaction value include:

- Benin

- Cameroon

- Chad

- Ghana

- Nigeria

- Tanzania

- Uganda

- Zimbabwe.

Types of taxes on DFS transaction amount differ by country

Some countries have specific taxes on money transfers (e.g. Ghana, Nigeria and Zimbabwe).Others tax both transfers and withdrawals (e.g. Benin, Cameroon, Chad, and Tanzania).

Uganda, on the other hand, taxes withdrawals but not transfers.

The taxes vary on several dimensions:

- the rates of tax

- the types of payment that are exempt

- tax-free thresholds at the lower end

- tax caps at the higher end.

Tax rates

Among countries that have imposed a percentage tax on transactions, the rate ranges from 0.2 per cent to 5 per cent.

Nigeria takes a different approach, with a singular and one-off levy on money transfers. That means, regardless of how much money you transfer, a fixed levy applies.

Benin and Tanzania apply their levy depending on the amount transferred or withdrawn. Since introducing the tax, the Tanzanian government has lowered the rates several times.

Tax exemptions

Cameroon and Chad have chosen to exempt bank-to-bank transfers and tax payments.

Ghana excludes, among others, tax payments and payments made to or from formal enterprises.

Tax-free thresholds

Tax-free thresholds vary across countries. Ghana, Nigeria, Tanzania, and Zimbabwe tax only transactions that surpass a certain threshold, whereas the other countries tax DFS regardless of how small the amount.

Tax-rate caps

At the other end of the scale, Benin, Tanzania and Zimbabwe have chosen to cap the tax rate. Above a particular threshold, the tax rate no longer increases.

Tax types and rates on transactions made via digital financial services in Africa (January 2023)

Comparing taxation of DFS transaction amount with that of traditional banking

Many countries tax digital and traditional financial services differently. For example:

- Uganda’s tax applies only to withdrawals of mobile money (transactions made via mobile phones, known as MM, standing for ‘mobile money’), and thus targets only MM consumers, but not users of other non-digital financial services, such as cash withdrawals from banks.

- In Cameroon and Chad, taxes apply to all financial services delivered digitally, but bank transfers are explicitly exempt from the electronic money transfer tax.

- Benin’s tax applies to electronic money transfers and withdrawals provided through public networks, and is collected only by telcos (telecommunication companies).

Looking more closely at Ghana’s and Tanzania’s taxes reveals how the various exemptions and different tax bases create an unlevel playing field:

- Ghana’s e-levy mainly targets MM transactions. The tax-free threshold for bank-account transfers is GHS 20,000 (USD 1,819), whereas the daily cumulative tax-free threshold for MM transactions is only GHS 100 (USD 9.09). Different transactors are also treated differently. Payments made by businesses directly from their bank accounts are exempt from the e-levy, regardless of who the recipient is.

- Tanzania’s levy on electronic money transfers initially applied to MM transfers, transfers from an MM account to a bank (and the opposite way), and bank-to-bank transfers. The cancellation of the latter two was announced on 20 September 2022, meaning that now the levy exclusively applies to transactions made via mobile phones.

Other countries, such as Nigeria, tax financial services delivered through digital channels by focusing on electronic money, which can be delivered by banks or telcos.

Only one country taxes digital and traditional financial service delivery methods equally. In Zimbabwe, financial institutions pay the Intermediated Money Transfer Tax on behalf of their clients, whenever they mediate money transfers in ways other than by cheque. The government considers any banking institution as defined in the Banking Act, and any telcos providing mobile money services, as a ‘financial institution’.

Levelling the playing field

An uneven playing field, in which DFS, in particular, are taxed more highly, should prompt policymakers to think carefully about the impacts of different tax regimes for several reasons:

- It affects the competition between DFS providers and other financial service providers.

- It may have negative effects on lower-income consumers, to the extent that they disproportionately use DFS.

- Different tax treatments of digital and non-digital transactions can incentivise cash payments over digital payments.

Unless there are clearly laid-out and compelling reasons to do otherwise, comparable financial services should typically enjoy the same tax treatment.

Levelling the playing field requires redesigning the tax in light of broader market conditions.

A thorough evaluation of how the tax system treats digitally delivered and traditionally delivered services also requires an assessment of the taxation of digital infrastructures and the different transaction fees charged for the services offered by different types of providers, which vary widely.

The author would like to thank Philip Mader for his valuable suggestions.