Ghana’s Minister of Finance recently declined to provide assurance that revenue from a new tax on digital financial services would not be collateralised. At a recent press conference, the Minister stated that he would examine the situation at hand and take a decision with cabinet on how to use resources.

Ghana’s Electronic Transfer Levy (E-Levy), set into implementation on the 1st of May, has been met with heated public criticism. Questions around its mechanisms of implementation remain, and in addition to public protest, the E-Levy’s constitutionality has been challenged in court. Ghana’s opposition NDC say they would repeal the E-Levy if elected in 2025. But this option might be foreclosed.

Ghana, like many other countries, is at risk of debt, inflation, and currency crises. In line with its Ghana Beyond Aid strategy, the government wants to avoid an IMF bailout . The new 1.5% E-Levy is set to be one of its tools. The Ghanaian government says the levy will mobilise revenue to support national development. But far from simply funding public services, as those paying the E-Levy might expect, the government might be considering using the revenue in a piece of financial engineering, known as collateralisation, to attract investors to help finance national projects. However, this may lead to a rigid and inefficient form of debt.

What is collateralisation?

Collateralisation, in a broad sense, is using an asset or something of value to make a loan less risky for the lender. We see it in our daily lives when houses are used as collateral for a mortgage loan. If whoever is borrowing the money is unable to pay what is due, then the lender can take the asset, or in this example the house, to cover any losses.

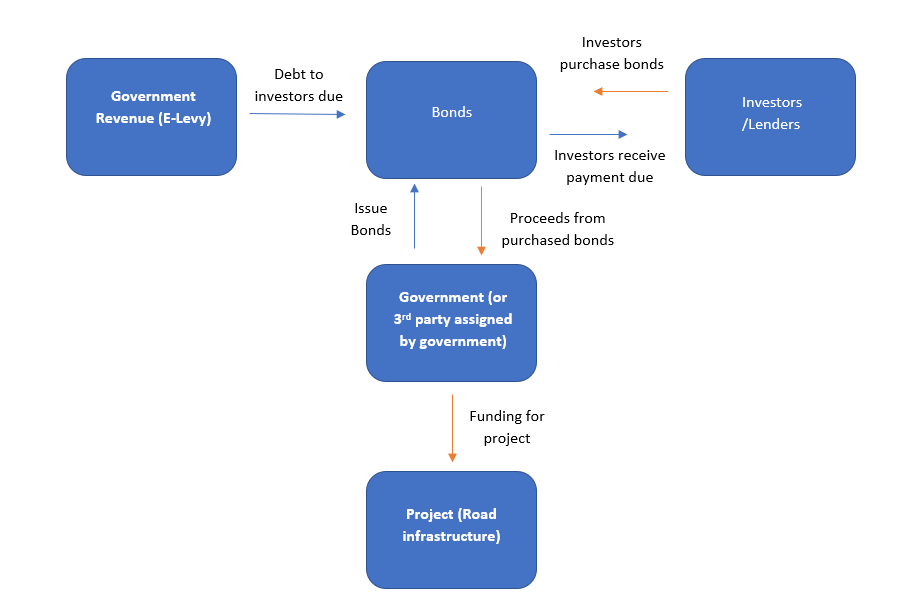

When it comes to using government revenue as collateral, it is a little different to the house example. In this case, the government will issue bonds collateralised or backed by some form of revenue stream (E-Levy revenue). Investors will then purchase the bonds giving the government money to finance a project or pay back a debt.

The investors will then receive money they are owed from the bonds through the designated revenue stream. In theory, collateralised bonds or loans should have a lower interest rate than uncollateralised bonds since there is less risk involved. Figure 1 gives a basic description of how collateralising the E-Levy revenue would work.

Figure 1

Source: Author’s own

Source: Author’s own

Where did this come from?

Earlier this year, Ghana abolished road tolls, apparently to reduce congestion. When questioned about reinstating the road tolls, the Roads Minister mentioned a plan to securitise revenue from the E-Levy which would then be used to finance a bond for infrastructure development. However, there doesn’t seem to be a settled view in the ministerial team on the matter.

The GRA’s website does indeed refer to road infrastructure as part of the rationale for E-Levy implementation but does not make any reference to collateralisation. According to the Ghana Revenue Authority (GRA,) the E-Levy’s goals fall into four categories: revenue mobilisation, support entrepreneurship, increasing Ghana’s tax to GDP ratio, and National Development. Support Entrepreneurship is intended to “raise revenue to support entrepreneurship, youth employment, [the] provision of digital infrastructure and cyber security, and [the] provision of road infrastructure.” As we can see, the provision of road infrastructure is one in a list of many purposes the E-Levy is meant to serve. However, no clear frameworks on how to achieve this have been mentioned in its legislation.

If collateralised, how might it look?

The E-Levy Act states, “The Commissioner General shall pay the Levy collected under this Act into the Consolidated Fund.” Since there are no current concrete plans for the revenue beyond being collected in the fund, we can turn to other instances of when Ghana has collateralised levies to see what may happen if the government decides to collateralise it.

For example, the Energy Sector Levies in Ghana are already collateralised. The Energy Sector Levy Act gives a clear indication of what percentages of different energy levies are allocated to specific accounts, their specific purposes, and by whom these accounts will be managed. A certain portion of the revenue collected from the levy is earmarked (set aside for specific purpose) to help issue energy bonds and repay energy service debts.

Assuming it works like the Energy Sector Levies Act securitisation, then a certain portion of the revenue from the E-Levy would be guaranteed to go into a separate account to repay investors – that is, buyers of the bond – and kept in escrow accounts. Any excess revenue collected would be held in a ‘lockbox’ to meet shortfalls in times of insufficient revenue, and the government would commit to financing any remaining shortfall up to a capped amount.

What are its political implications?

The concept of using tax revenue as collateral for securities is not a new one and is held by some to decrease risks for investors. Daniela Gabor explains in The Wall Street Consensus, that there is shift toward “development as de-risking” where governments move to de-risk asset classes such as bonds. In this case, future tax revenue streams would be used as low-risk collateral for loans from investors. In a recent tweet, Gabor explains, “Ghana would issue infrastructure bonds and ‘de-risk’ yield by promising bond holders that existing revenues from the E-Levy will be used to service that debt.”

According to Professor Godfrey Bokpin, a Finance Professor at Accra University, the implications are far-reaching. Were Ghana’s opposition to return to power in 2025, they may be prevented from repealing the levy if the government followed through with using the revenue from the E-Levy as collateral for an infrastructure loan in the meantime. Future governments would have more debt obligations to pay off, and fewer options to raise revenue.

Ghana has a long history of lively politics around taxes, especially around consumption taxes which have seen plenty of bargaining between state and society. If securitisation means that a tax introduced by one government is effectively insulated from future democratic debate – as Prof Bokpin is arguing – where does that leave tax politics?

It is important to remember however that if the opposition comes in to power and is adamant to remove the E-Levy, it is very likely that they will find a way. Also, if the terms of the bonds allow them to be paid off early, future governments have the flexibility to end the arrangement earlier than initially intended.

Is it worth it?

The main question here is whether or not collateralising the E-Levy will lead to an efficient form of debt. Regardless of whether the E-Levy will be collateralised, the government will need to take on more debt to fund projects. Is the energy sector levy model worth replicating for the E-Levy revenue? Several questions emerge when examining the Energy Sector Levy (ESL) example.

The first issue lies in the rigidity of overcollateralisation and the ‘lockbox’ feature. Investors often want strong assurance that their investments are more than covered by the collateralised revenue stream. Therefore, the percentage of the levy revenue allocated to the debt servicing fund is normally higher than needed. This is what we refer to as overcollateralisation. Furthermore, in the ESL Act, any additional revenue is placed in a ‘lockbox’, tying up revenue that could be used flexibly in different projects. What percentage of E-Levy revenues would be needed to effectively service these debts taking into consideration overcollateralisation needed to attract investors?

The second issue is in the pricing difference between the ESL and non-collateralised government bonds. As explained previously, the attractiveness of collateralising bonds is the lower yield needed to be paid by the government because the bond is considered lower risk. However, when comparing the ESL yields to those of other government bonds at the time they were issued, there does not seem to be much of a pricing benefit. For example, in 2017 7-year ESL bonds settled at 19% while other government bonds settled at 19.75%. Is there a pricing benefit from collateralising the E-Levy versus not collateralising or using the infrastructure as collateral? With the mentioned intentions of the opposition, how likely is the E-Levy to be accepted as a low-risk collateral if it is perceived to be a highly uncertain and politically contentious source of revenue? Would the asset, as a result, be an excessively expensive way to finance government borrowing?

Further questions

Several questions remain unanswered: Will collateralising part of the E-Levy revenue bring transparency through earmarked or escrowed accounts and by providing specific mechanisms for using the revenue? Will securitising the E-Levy revenues detract from other purposes of the E-Levy? What behaviour changes among users from the E-Levy has been anticipated in the revenue stream?

With Ghana’s ambitious goals for the E-Levy, it is clear that next steps must be taken carefully and thoughtfully. Without clear answers to the questions mentioned, collateralisation of the E-Levy may prove to an unnecessary risk that furthers the government from its intended goals.

On the 24th of June, the ICTD will host a webinar to discuss the E-Levy’s design, its implementation, and its effects as experienced by different parts of society. The webinar aims to establish the basic facts about the E-levy and the contending perspectives on it through a round table discussion.