With over 16,000 deaths globally and the number of cases growing each day, the calamitous impacts of the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) are already being felt. As the virus continues to spread, the human impact in the Global South has the potential to be catastrophic as it strains weak and underfunded health systems. The economic impacts will also be devastating, with preliminary estimates predicting an income shortfall of $220 billion in developing countries (excluding China) and a GDP decrease of at least $25 billion in Africa.

While secondary to the public health emergency, it is important to consider how the pandemic will affect tax revenues in the Global South, given that these are critical to providing public services and achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. While governments anticipate losing revenue from a range of sources, local taxation is particularly vulnerable and affects a larger proportion of taxpayers in low-income countries than direct central government or trade taxes.

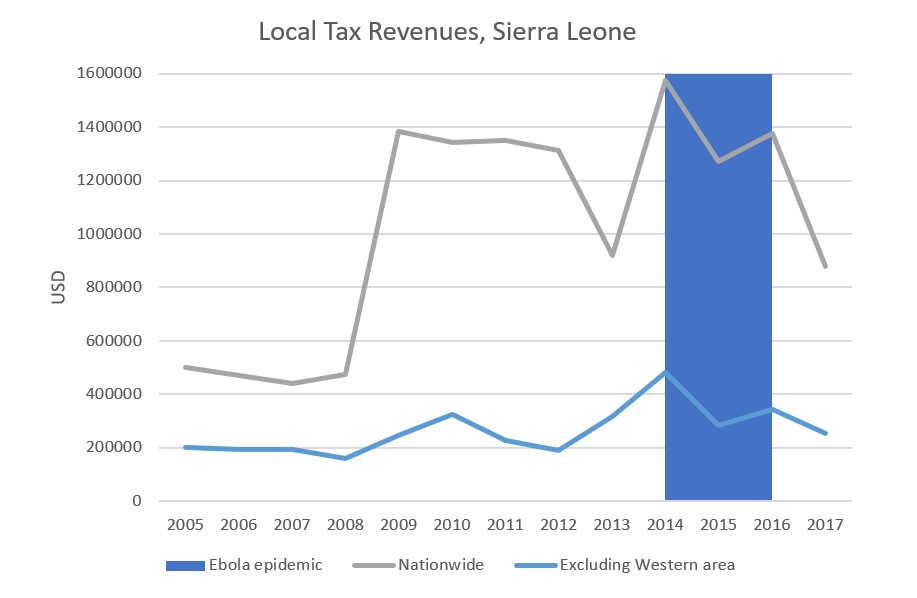

Sierra Leone’s catastrophic experience of the Ebola epidemic—which killed more than 3,900 people in Sierra Leone alone—offers an important case study of the impacts on local government revenues and the fiscal burdens of ordinary citizens. The indirect economic effects of the crisis were significant, with individuals losing livelihoods, governments losing the capacity to fund basic services, and individuals and communities bearing a greater direct cost of public goods provision.

Although no cases of COVID-19 have been reported in Sierra Leone yet, there are cases in neighbouring Guinea and Liberia and, as President Bio declared in a national address last week, “It is no longer a question of whether the Corona Virus will come to Sierra Leone, it is a question of WHEN.”

Anatomy of an epidemic’s effect on local government revenue

In Sierra Leone, local government tax revenues unsurprisingly fell during the Ebola epidemic. Although the revenue losses were fairly small in absolute terms, their impact was significant given the low baseline. Indeed, from 2005 to 2017, local governments collected tax revenue amounting on average to only 17 cents per capita — so little that they could barely do more than pay for basic administrative costs. And the fiscal situation is much worse outside the relatively high-revenue Western area (the capital, Freetown, and the surrounding Western Area Rural district). In the provinces, where 79% of the population lives, local tax revenue amounted to on average only 6 cents per capita per year over the same period. With this baseline, any revenue loss can have devastating impacts on local governance and service delivery.

Local taxes and revenues decreased for three key reasons:

- Some local revenues were simply no longer available due to economic lockdowns and social distancing containment measures. For example, markets were closed during the crisis, leaving the government unable to collect market fees and rents in some areas. This was significant as market dues made up on average 23% of total local revenues from 2005 to 2016. Due to COVID-19, the Sierra Leonean and sub-national governments are currently taking preventative containment measures that may similarly limit economic and taxable activity, including restricting market and street trading hours and banning gatherings of more than 100 people. These containment and social distancing measures are likely to only get more stringent.

- With schools, markets, and many businesses closed during the Ebola crisis, many citizens faced extreme economic hardship. In response, local governments issued an effective amnesty on the most commonly paid tax at the local level—the local (poll) tax that is levied on all adults. In my interviews with local government officials, I found that this was based in part on moral economy justifications that it was simply not right to make people pay. Similar justifications were used to explain the non-collection of other local taxes, with leniency of enforcement being a normal, if ad hoc and informal, response to the economic situation.

- As a result of the lack of online infrastructure for tax assessment and payment, many local taxes became too risky to collect. For property taxes, for example, tax bills are delivered by hand to individual properties and all payments must be made in person at banks or the local government office. Face-to-face interaction goes from being an inconvenience and accountability risk in normal times to a major public health risk during times of contagion.

A public crisis increases individual burdens

While local government tax collection efforts diminished significantly during the Ebola crisis, citizens were not relieved of their fiscal burdens. Indeed, Sierra Leoneans contribute considerably to public goods provision and community mobilization efforts through user fees and informal taxation—and have to do so to a greater extent when local services are underfunded.

Sierra Leone’s public health system is woefully underfunded, with a significant proportion of financing coming from user fees. Not only does this discourage low-income individuals from accessing healthcare, it means that individuals bear a significant part of financing the health system. Public clinics often have nurses and staff that are not on government salaries or receive delayed salaries, which results in the common practice of charging extra fees or having bribes or non-monetary “gifts” effectively required in order to access treatment and essential medicines. In a survey of taxpayers in eastern and northern Sierra Leone conducted in 2017, for example, I found that more than a fifth of individuals had made informal payments to doctors or nurses in the previous year and more than a fifth had contributed labour for the construction or maintenance of public health facilities.

At the same time, donor funding during and immediately after the Ebola epidemic shifted from funding public services like education to emergency humanitarian and public health needs. While evidently necessary, this shift in aid funding resulted in shifting the burden of financing local public goods and services— including schools, teachers, and water wells—onto individuals and communities.

The additional burden on citizens is regressive

Shifting the financial responsibility of essential services, governance, and public infrastructure from the state onto citizens results in inequitable outcomes: The degree and quality of access to public goods depends on the relative wealth of a particular area and access to essential goods depend on the ability to pay. Moreover, as user fees and informal taxes are generally charged at a flat rate, they are overwhelmingly regressive, while my research further shows that the burden of user fees and informal taxes is significantly higher for women.

Communities also shouldered much of the burden of the crisis response

While there was a massive increase in international aid during the Ebola crisis, individuals and communities contributed substantially to crisis response efforts. Traditional authorities were central in containment efforts, introducing chiefdom level by-laws to restrict movement and activity; community tracers were critical in identifying at-risk individuals; and community patrols were vital to preventing the movement of people within and across the most affected areas. Though in some areas chiefs received substantial international support, they also relied on communal labour and contributions to support local mobilization efforts. As explained to me by a District Council Chairman during my research, much of the effort was “self-funded, through… the people.”

The burden was exacerbated by the unfortunate fact that millions in emergency funds went missing, leaving frontline officials and response teams unpaid—and thus reliant on community support and contributions to get by. Such contributions, while they may have added to the burden of regular people during a difficult time, were a central part of the community mobilization that allowed the country to eventually overcome the epidemic.

Lessons for COVID-19

While the current global pandemic is unique in many respects, in the Global South it is also likely to have significant direct health effects, in terms of loss of life, and indirect economic effects, including individuals losing livelihoods and governments losing the capacity to fund basic services. While public health and security concerns are of course paramount, the Ebola epidemic in Sierra Leone demonstrates how the negative effects for vulnerable populations are compounded when local governments are forced to cut back on services and individuals are effectively made to bear a greater cost of public goods provision through user fees and informal taxes.

While international policymakers’ first priority is to contain the pandemic, they can also learn valuable lessons from West Africa’s experience with Ebola in order to minimise the real costs for citizens of developing countries in the short and long-term:

- Urgently provide crisis response financing: The international response to the Ebola crisis was slow to arrive, after the epidemic had already spiralled out of control. While the IMF and World Bank have announced $50 billion and $14 billion in global financing, respectively, far more will be needed—and quickly—in grants and low- and no-interest loans, to not only address the health emergency but provide critical cushioning for the economic impacts.

- Measure impacts to tailor the response: Systematic crisis monitoring is crucial for enabling governments to target support and mitigate the most severe effects for vulnerable groups. During the Ebola epidemic for example, researchers made use of existing sampling frames to conduct mobile phone surveys, gathering almost real-time data on which households and businesses were experiencing the greatest health and economic hardships. The willingness and capacity of donors and researchers to similarly be agile and adapt programmes to meet new and pressing data collection objectives will be particularly important to systematically measure and respond to the impacts of COVID-19.

- Invest in health systems now: Unfortunately, the lessons from Ebola did not translate into the required investments in public health systems and pandemic preparedness. Only 3% of international recommendations for financing preparedness efforts have been achieved by the international community, with 50% seeing little to no progress. A review by the World Bank estimates that it would cost on average $1.69 per capita to finance appropriate pandemic preparedness in low- and middle-income countries. In the long-term, this implies that countries need to strengthen equitable taxation in order to ensure sustainable financing for public health and other essential goods in the future. Otherwise, my research shows that where there are financing shortfalls, individuals and communities will fill the gaps and feel the pain.

Rhiannon McCluskey, ICTD Research Uptake and Communications Manager, provided invaluable contributions to the writing of this blog.