Ghanaian President John Mahama’s government presented its much-awaited 2025 budget last month. In it, Finance Minister Cassiel Ato Forson outlines his plan to fund campaign promises, including the flagship 24-hour Economy strategy and the “no academic fees” policy. The budget includes the cancellation of several unpopular taxes introduced by the previous government—such as the Electronic Transfer Levy (“E-levy”), the Covid-19 levy, VAT on select categories, and the betting tax.

Ghana’s move follows a broader regional trend. Malawi and Tanzania have similarly face challenges in implementing digital taxes, ultimately scaling them back. More recently, governments in South Africa and Kenya also scrapped or reduced contentious tax measures in response to public pressure and economic concerns.

Some of the scrapped taxes were introduced under the umbrella of the New Patriotic Party (NPP) government’s “Ghana beyond Aid” agenda, which aimed to reduce reliance on foreign donors through increased domestic revenue mobilisation, economic diversification, and agricultural modernisation. The e-levy, that slapped a 1.5% tax on mobile money transfers, was widely unpopular and seen as regressive as it disproportionately affected lower-income Ghanaians using mobile money in the informal economy. The government also raised the standard VAT rate from 12.5% to 15%. While these levies were unpopular, they allowed the government to raise much needed revenue and expand its tax base, especially during a post-pandemic era when the country struggled to service its ballooning debt amid rising inflation and a weakening currency. According to one estimate, the e-levy constituted about 1.06% of total tax revenue collected in 2023, less than it was originally projected to contribute, but an important source nonetheless.

The Government’s Difficult Balancing Act

However, no government can have its cake and eat it too. As it scraps these taxes, the government faces a looming debt crisis. A total of $8.7 billion due by 2028, a spiralling debt-to-GDP ratio, and IMF involvement, place explicit conditions on how the government needs to run its fiscal house. Mahama’s government is therefore in a difficult position as it tries to find alternative sources of revenue to replace the income lost from the scrapped taxes.

But as leaders across the world have now realised, managing the country’s debt and raising revenue is a politically challenging ordeal. Opposition figures and industry groups have warned that scrapping taxes risks undermining revenue targets and should not be used to justify raising other taxes. Voters, often fed up with the high cost of living and stagnating economic growth, have limited appetites for new taxes and spending cuts. Some leaders may therefore be tempted to use rhetorical strategies like nationalist appeals to promote fiscal reforms, while others may opt for a more transparent approach and present upfront the short-term pains of reforms.

An online experimental study I conducted last year with 1,041 Ghanaian citizens from across the country dug into these strategies.

Transparency, not Rhetoric, is the Government’s Best Long-Term Strategy for Fiscal Reforms

My study finds that transparency about the costs of reforms makes voters more willing to support them. This is applicable both for tax increases (like VAT) and new ones (like e-levy). Rather than relying on broad, nationalistic narratives that obscure the true fiscal implications, providing transparent information on the costs associated with tax reforms can help clarify their necessity and benefits, thereby fostering public support, trust and compliance. Voters who receive detailed cost information may perceive the policy as more credible and view the sacrifices as justified investments for the nation’s future. This finding is consistent with a 2021 Afrobarometer study suggesting that Ghanaians were willing to pay more taxes for national development but desired increased transparency about taxes and spendings. The importance of transparency in building public trust and support for fiscal reforms has been echoed by the IMF. Other research by ICTD likewise suggests that fiscal transparency requires not only accessible information but one relevant to taxpayers’ daily lives and priorities. Yet, taxpayer education is severely lacking in many parts of Africa.

Partisanship doesn’t Explain Policy Support Either

Prior research shows that partisanship can distort economic perceptions as partisans selectively assign blame and credit through motivated reasoning when confronted with economic facts. Yet my findings suggest that exposure to nationalistic framing or cost information did not significantly alter support along party lines. This may be because these strategies work similarly across partisan divides—or because fiscal reform, when clearly explained, resonates beyond party affiliation.

Since the Ghana Beyond Aid (GhBA) agenda, introduced by President Nana Addo Dankwa Akufo-Addo, was part of the NPP government’s economic vision and branded as such, I tested whether the positive effects that providing cost information has on support are concentrated only among NPP supporters. I found no such effect. Presenting these austerity policies (tax increases, temporary price hikes from import substitution) through a nationalist rhetoric or with detailed cost information did not disproportionately increase support among NPP supporters. The effect I find of cost transparency cuts across party lines. National Democratic Congress (NDC), NPP, and swing or third-party supporters all responded to the cost information favourably.

Less-educated voters are Particularly Vulnerable to Populist Appeals around Fiscal Reforms

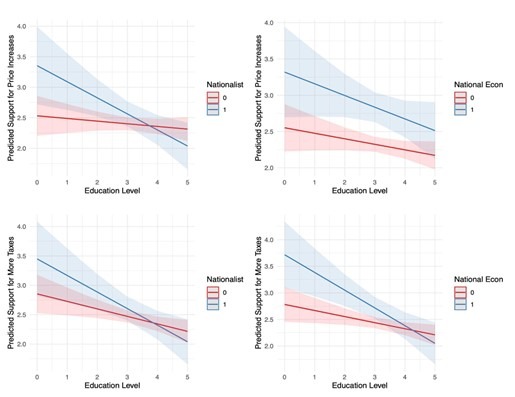

As the figure below shows, I find that the nationalist rhetoric around GhBA is most effective at raising support for taxes and temporary price increases among lower-educated voters in my sample. These voters were more willing to support such policies when they were framed nationalistically instead of in plain terms. In contrast, more-educated voters tend to be more sceptical of the government’s rhetoric.

That being said, I also found that combining nationalist framing with cost information raises economic anxiety about the future among less educated citizens. Thus, while rhetorical strategies may mobilise this category of taxpayers, their heightened economic insecurity can backfire for incumbents, especially when a large share of the population has relatively low education.

The Past Offers Lessons for the Present

Ghana’s political history illustrates the use of both rhetorical strategies and detailed public education to minimise opposition and implement challenging fiscal reforms at various times. During the 1980s and early 1990s, under General Jerry Rawlings’s military rule, structural adjustments and economic recovery reforms were sold through nationalist populism. At the time, Ghana had initiated the Economic Recovery Program (ERP) which enforced fiscal spending cuts to lower budget deficit, currency devaluation to boost exports, and slashed public sector jobs.

When announcing the reforms, Rawlings emphasised that the priorities of rural farmers had been overlooked, framing devaluation as a nationalistic policy aimed at reducing Ghana’s “psychological dependence on foreign imports” and uplifting domestic producers. Scholars of Ghana’s political economy credited Rawlings’s government with balancing populist nationalism with free-market reforms. This is not to say that these reforms faced no opposition. Still, a combination of nationalist populist rhetoric, authoritarian crackdowns, and international donor support enabled the structural reforms to be implemented.

However, after Ghana’s democratic transition, the limitations of populist rhetoric within a democratic society became increasingly clear. Rawlings’s government attempted to introduce a VAT in 1995 but was met with strong public opposition and large-scale protests. It was successfully reintroduced in 1998 only after a comprehensive public education campaign that offered detailed cost information to citizens through seminars, media outreach, and engagement with trader associations by the government. In his book, Wilson Prichard notes that this direct tax bargaining over VAT in Ghana led to an expansion in democratic accountability in the country’s Fourth Republic.

Ultimately, public accountability is greater in a democratic system. The government’s best bet to implement fiscal reforms is to clearly convey their costs and benefits to the public. My study’s results suggest that this holds as true for fiscal policies today as it did in the 1990s.