British civil servants sign up to core values enshrined in the Civil Service Code: integrity, honesty, objectivity and impartiality. Implicit in these is evidence-based practice, which in turn suggests the need for a steady flow of relevant research.

Although I have been reading research during many years working in DFID, it was only when I moved to a role commissioning and managing governance research that I realised just how much research is being done – and how much I had to learn about it.

One of the areas that DFID is increasingly focusing on is tax research, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, as we want to help African governments raise their own revenues and reduce their need for aid. This is part of the Addis Tax Initiative (ATI), which the UK helped co-found, and which committed donor countries to double their efforts on developing tax capacity, alongside a commitment from partner countries to step up their efforts in raising taxes to finance sustainable development.

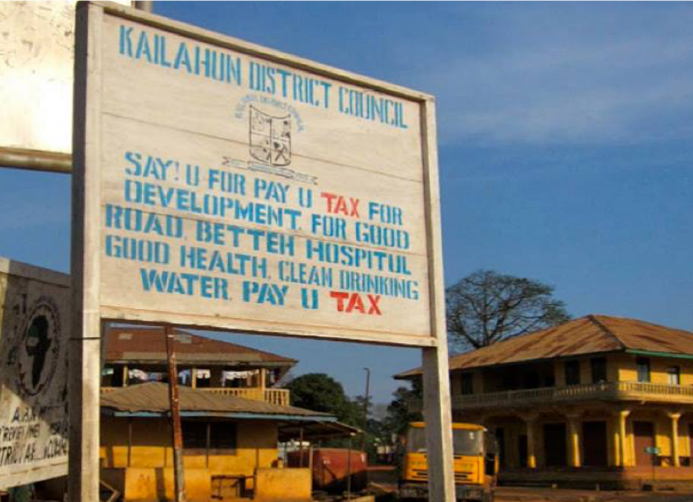

Yet taxation is about far more than just raising revenue – it is inextricably linked with processes of state-building and politics. Increased taxation has the potential to spur popular demand for government accountability, leading to better governance. This is a crucial area of research for the DFID-supported International Centre for Tax and Development (ICTD), and this blog, written with the help of Rhiannon McCluskey of ICTD, summarises some of the recent findings presented at the Centre’s annual conference held in Rwanda.

The Theory

As Dr Roel Dom of ICTD explained in his presentation, there is a well-established link between taxation and accountability in the revolutions of the 17th and 18th centuries in West. The theory is that when citizens are forced to pay taxes, they are more likely to feel ownership of government revenues and demand benefits in return, while governments in need of revenue are more likely to make concessions to those taxpayers in order to encourage tax compliance. This process of tax bargaining can lead to more responsive and accountable governance.

However, for contemporary developing countries this connection is less clear, as their circumstances are very different. Many African countries have access to alternative sources of revenue in the form of natural resource rents or aid, and governments have access to a wider set of tax policy tools with varying levels of saliency for taxpayers (an important determinant of engagement). In Nigeria for example, 65% of government revenue comes from the oil and gas sector, and the ‘tax morale’ (people’s attitudes towards paying taxes) of citizens is extremely low. New data reveals that more than a fifth of Nigerians think it is ‘not wrong at all’ to not pay taxes on income, while over half thought it was ‘wrong but understandable.’

How, then, can positive connections between taxation and accountability be strengthened?

In order to improve tax morale and compliance, taxpayers need to understand the taxes they pay, why they pay them, and how the revenues are used. With this awareness and information, they might be more motivated and better equipped to make demands on government. However, in many African countries, taxpayers find it difficult to know:

- What taxes they owe – 48% of Nigerians said that getting information about what taxes to pay and how to pay them is difficult or very difficult.

- How to pay – In Rwanda, 60% of a sample of new taxpayers (mostly businesses) said that it was difficult to file a return, and 33% said that it was difficult to get in touch with the revenue authority.

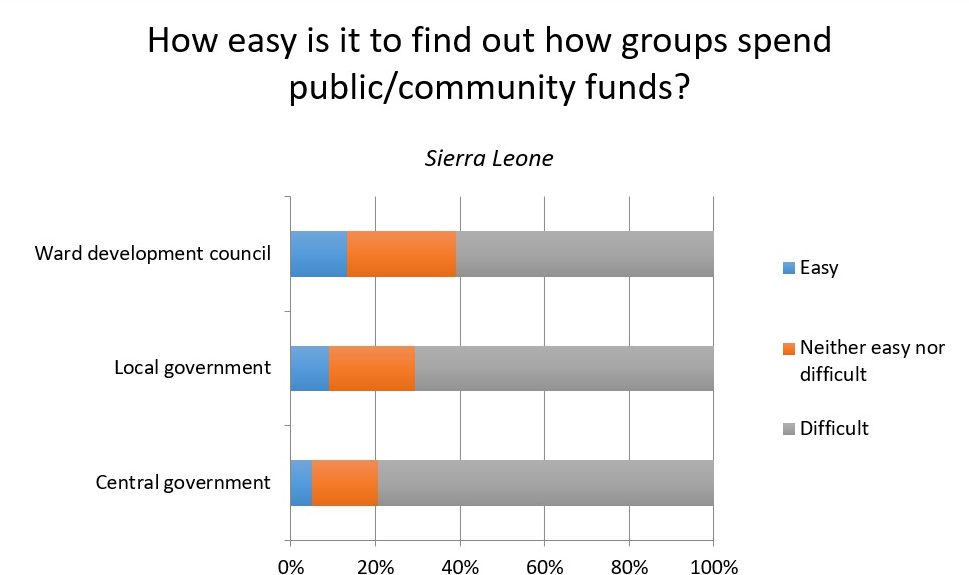

- What those taxes are used for – In Sierra Leone, 59% of respondents at the ward level had difficulty finding out how government spent public funds, and this rose to 63% at the local and 76% at the central government level.

Increasing transparency and engagement around taxes

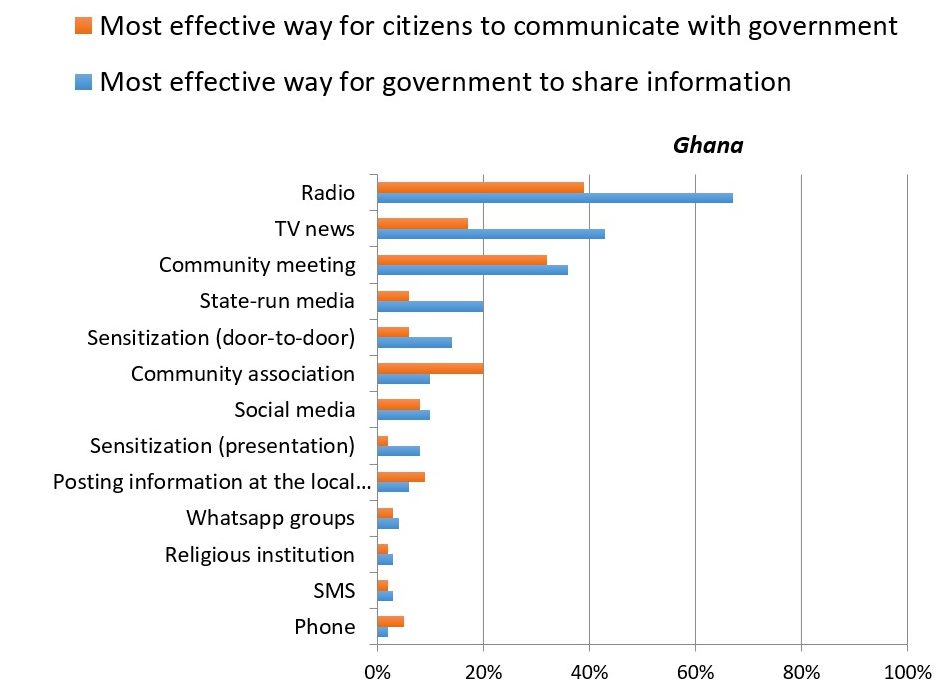

Research in Sierra Leone and Ghana investigated the efficacy of efforts to increase transparency and popular engagement around taxes. The surveys found that in order for the information to be meaningfully transparent, it should be:

- Timely,

- Accessible (e.g. in local languages),

- Specific to taxpayers’ needs (e.g. info on rates and payment due dates), and

- Linked to expenditures (local public services).

The study found that the most popular means of providing information were those with an element of interaction, particularly radio shows. The research suggests that there is much that governments at all levels can learn about the information needs of citizens, how best to present information, and how to better link revenue collection to public expenditures.

There is also an important role for civil society to play, as Andrew Itai Chikowore presented. Civil society organisations such as the Tax Justice Network Africa, can assist in translating complex tax and spending issues, help citizens understand their rights and responsibilities, and help them in developing collective demands as well as facilitating constructive engagement in public forums.

Future Research

Although there is mounting evidence that increased taxation is indeed linked with greater accountability in Africa, there is a need for further research to identify concrete strategies for linking taxation and good governance at both the local and national levels. Some questions the ICTD is hoping to answer in the next few years include:

- What methods work to build voluntary tax compliance in situations where the social contract is fundamentally weak?

- What is the role of taxpayer education and knowledge in building a culture of tax compliance and accountability?

- What are the most effective ways of increasing the tax literacy of smaller taxpayers and their engagement in policymaking?

- What are the most effective forums for allowing civil society to engage with, and put pressure on, governments? And what strategies are most effective for encouraging governments to respond positively?

Answering these questions will help inform DFID and other donor tax programs, ameliorate government taxpayer outreach efforts, and shape civil society engagement strategies in ways that will increase the likelihood of tax collection translating into the provision of enhanced public goods and services and stronger social contracts.

To learn more, see the ICTD Summary Brief What have we learned about taxation, state-building and accountability?

Follow @DFID_Research for the latest DFID research news, jobs and funding.

Follow @ICTDTax for the latest research on tax policy and administration in sub-Saharan Africa.

Read the version published by DFID Research on Medium here.